- 1Pediatric Department, College of Medicine, King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia

- 2Division of Infectious Diseases, Department of Internal Medicine, College of Medicine, King Saud University and King Saud University Medical City, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia

- 3College of Medicine, King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia

- 4Critical Care Department, College of Medicine, King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia

- 5Division of Pediatric Cardiology, Department of Cardiac Sciences, College of Medicine, King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia

- 6Heart Center, King Faisal Specialist Hospital & Research Center, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia

- 7Sharjah Institute of Medical Research, University of Sharjah, Sharjah, United Arab Emirates

- 8Department of Community and Family Medicine, College of Medicine, University of Sharjah, Sharjah, United Arab Emirates

- 9Dr Sulaiman Al Habib Medical Group, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia

- 10Department of Medicine, College of Medicine, Qassim University, Qassim, Saudi Arabia

- 11Department of Clinical Sciences, College of Medicine, University of Sharjah, Sharjah, United Arab Emirates

- 12Department of Family and Community Medicine, King Saud University Medical City, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia

- 13Evidence-Based Health Care & Knowledge Translation Research Chair, King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia

- 14College of Pharmacy, Alfaisal University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia

- 15Department of Psychiatry, College of Medicine, King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia

- 16Department of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine, College of Medicine, King Saud University and King Saud University Medical City, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia

- 17Specialty Internal Medicine and Quality Department, Johns Hopkins Aramco Healthcare, Dhahran, Saudi Arabia

- 18Infectious Disease Division, Department of Medicine, Indiana University School of Medicine, Indianapolis, IN, United States

- 19Infectious Disease Division, Department of Medicine, Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Baltimore, MD, United States

Background: Healthcare workers' (HCWs') travel-related anxiety needs to be assessed in light of the emergence of SARS-CoV-2 mutations.

Methods: An online, cross-sectional questionnaire among HCWs between December 21, 2020 to January 7, 2021. The outcome variables were HCWs' knowledge and awareness of the SARS-CoV-2 B.1.1.7 lineage that was recently reported as the UK variant of concern, and its associated travel worry and Generalized Anxiety Disorder (GAD-7) score.

Results: A total of 1,058 HCWs completed the survey; 66.5% were female, 59.0% were nurses. 9.0% indicated they had been previously diagnosed with COVID-19. Regarding the B.1.1.7 lineage, almost all (97.3%) were aware of its emergence, 73.8% were aware that it is more infectious, 78.0% thought it causes more severe disease, and only 50.0% knew that current COVID-19 vaccines are effective in preventing it. Despite this, 66.7% of HCWs were not registered to receive the vaccine. HCWs' most common source of information about the new variant was social media platforms (67.0%), and this subgroup was significantly more worried about traveling. Nurses were more worried than physicians (P = 0.001).

Conclusions: Most HCWs were aware of the emergence of the SARS-CoV-2 B.1.1.7 variant and expressed substantial travel worries. Increased worry levels were found among HCWs who used social media as their main source of information, those with lower levels of COVID-19 vaccine uptake, and those with higher GAD-7 scores. The utilization of official social media platforms could improve accurate information dissemination among HCWs regarding the Pandemic's evolving mutations. Targeted vaccine campaigns are warranted to assure HCWs about the efficacy of COVID-19 vaccines toward SARS-CoV-2 variants.

Introduction

The emergence of the Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) has resulted in a global pandemic. Being an RNA virus, SARS-CoV-2 can mutate over time, and thus multiple SARS-CoV-2 variants are circulating globally (1). As of December 13, 2020, there were 1,108 reported cases of people infected with the B.1.1.7 variant in the United Kingdom (UK) in almost 60 different local authorities, with the exact number likely much higher (2). The UK variant under investigation in this study was discovered in December 2020 (VUI-202012/01) and is characterized by a set of 17 mutations (2). One of its most significant mutations is N501Y in the gene coding of the spike protein, which attaches to the angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 receptors (2).

The B.1.1.7 lineage was first identified by the COVID-19 Genomics UK consortium, which performs random genetic sequencing of positive COVID-19 samples in the UK. Since its creation in April 2020, the consortium has sequenced 140,000 virus genomes from individuals infected with COVID-19 and publishes weekly reports on its website (3). This B.1.1.7 variant is estimated to have first emerged in the UK in September 2020 (1). As the variant rapidly spread in the subsequent few weeks, by December 26, 2020, more than 3,000 cases of this new variant have been reported in the UK (4).

This mutation has been found to have a high transmission rate and has become one of the main circulating variants in several locations in the UK (2). This variant has since been detected in many other countries around the world, including the United States (U.S.) and Canada (1). The European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC) recommends that residents of the most affected areas restrict movement and travel, including international travel outside of these areas (4). Several countries, including the UK, have imposed travel restrictions to limit the variant's rapid spread (4).

Scientists and researchers have begun to learn more about this variant to better understand its virulence and infectiousness and whether currently authorized COVID-19 vaccines would illicit immunity against it (1). The rapid spread of B.1.1.7 has prompted the ECDC to announce that the overall risk associated with the introduction and further spread of this SARS-CoV-2 strain is high (4). Despite the current lack of evidence that these variants may cause a more severe illness or increased risk of death, healthcare workers (HCWs) are yet again challenged by a new stressful situation that could affect their psychological well-being and/or travel arrangements (1, 5).

The Kingdom of Saudi Arabia (KSA) took multiple steps to decrease the spread of COVID-19, including the following: suspending the country's eVisa program and placing a ban on inbound travel, including the neighboring Gulf countries. In addition, on March 7, 2020, KSA limited international flights to the three major airports within the Kingdom and required a negative PCR test for SARS-CoV-2 for arriving travelers (6). The rapid spread of this new strain has prompted stricter international travel bans to and from affected countries (from December 21, 2020, to January 7, 2021). The closure of airports and restrictions to travel are likely to cause panic and concerns, particularly among healthcare workers, where two-third of healthcare workers in KSA are expatriates (7). To date, all international flights remain very limited to essential workers such as healthcare workers. Media outlets have announced that many non-Saudi expat HCWs have been stranded abroad and are still struggling to return to the KSA, with available flights in short supply (8). The emergence of the new strain is expected to introduce further restrictions making travel even more difficult, thus potentially causing anxiety and concerns among this group. Also, baseline higher anxiety levels were reported to be more common in medical personal, especially female doctors and nurses (9). Starting on December 17, 2020, Saudi Arabia has rolled out mass BNT162b2 vaccinations for HCWs, with open registration beginning a week earlier (10). As the rapid evolution of the situation warrants further research, we conducted this study among HCWs in Saudi Arabia to assess their perceptions, anxiety levels, and travel worries caused by this new SARS-COV-2 variant. We hypothesized that the presence of underlying generalized anxiety, lack of awareness of new B.1.1.7 variant, and personal risk factors for severe COVID-19 infections (e.g., older age) might contribute to increased worry level of travel.

In this study, we examined the awareness HCWs in Saudi Arabia of the new B.1.1.7 SARS-COV-2 variant, utilizing several variables that may contribute to their awareness of the new variant spreading across international borders, imposing additional risks upon international travel, and ultimately imparting to the fear and anxiety surrounding travel and its recent restrictions. The variables assessed in our study included gender, age, nationality, level of education, and profession. Moreover, we attempted to link these factors to the level of anxiety, travel perception, personal and professional experience of dealing with COVID-19, and the source of knowledge.

Method

Data Collection

This multicenter, cross-sectional survey was conducted among HCWs in Saudi Arabia during the COVID-19 pandemic. Data were collected between December 27, 2020 and January 3, 2021. At the time of data collection, there were at least a handful of countries that had reported infection with the B.1.1.7 variant of SARS-CoV-2. HCWs were surveyed regarding their perceptions, anxiety levels, and travel worry caused by the new variant. Participants were invited using a convenience sampling technique. We used several social media platforms and email lists to recruit participants. The survey was a pilot-validated, self-administered questionnaire that was sent to HCWs online through SurveyMonkey©, a platform that allows researchers to deploy and analyze surveys via the web. The questionnaire was adapted from our previously published study with modification and additions related to the new SARS-COV-2 variant (11–13).

The questions asked about respondents' demographic characteristics (job category, age, sex, years of clinical experience, and work area), previous exposure to COVID-19 patients, travel history in the previous 3 months, and whether they had received and/or registered to receive the COVID-19 vaccine. We assessed the following outcomes related to the new SARS-COV-2 variant: knowledge, perceptions, and travel worries. In addition, we assessed factors affecting respondents' worry level regarding international travel as well as HCWs' sources of information about the B.1.1.7 SARS-CoV-2 mutant variant. HCWs' anxiety was also measured by the validated 7-item General Anxiety Disorder (GAD-7) questionnaire, which has been used in several studies assessing HCWs' anxiety levels during the pandemic (12, 14).

HCWs were informed of the purpose of the study in English at the beginning of the online survey. The respondents were given the opportunity to ask questions via a dedicated email address for the study. The Institutional Review Board at the College of Medicine and King Saud University Medical City approved the study (approval #20/0065/IRB). A waiver for signed consent was obtained since the survey presented no more than a minimal risk to subjects and involved no procedures for which written consent is usually required. To maximize confidentiality, personal identifiers were not required.

Statistical Analyses

Descriptive analyses using means and standard deviations were applied to continuously measured variables, and categorically measured variables were described with frequencies and percentages. The histogram and the statistical Kolmogorov–Smirnov tests of normality were used to assess the statistical normality of the measured continuous variables. The multiple response dichotomy analysis was applied to the multiple option questions, such as the one asking about sources of information. Respondents' awareness of the new mutagenic SARS-COV-2 virus strain was measured with eight questions, which received a score of 1 for each correctly answered knowledge/awareness question and 0 for incorrectly answered questions. A total awareness of mutagenic viral outbreak score was measured by adding the scores for the knowledge indicators (range: 0–8 points). For categorically measured variables, the independent samples t-test and one-way ANOVA test were used to assess the statistical significance of HCWs' mean perceived worry regarding travel. Pearson's bivariate test of correlation was used to assess the correlations between metric variables. Multivariate linear regression analysis was used to assess the multivariate associations of HCWs' demographic and professional characteristics and their perceptions with their worry level about traveling abroad.

The collinearity & multicollinearity between independent variables were tested using bivariate correlations, variance inflation indices factor (VIF), and tolerance statistics. These parameters were within an acceptable range. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 21.0. Armonk, NY: IBM Corp. was used for the statistical data analysis, and results were considered significant at the 0.05 level.

Results

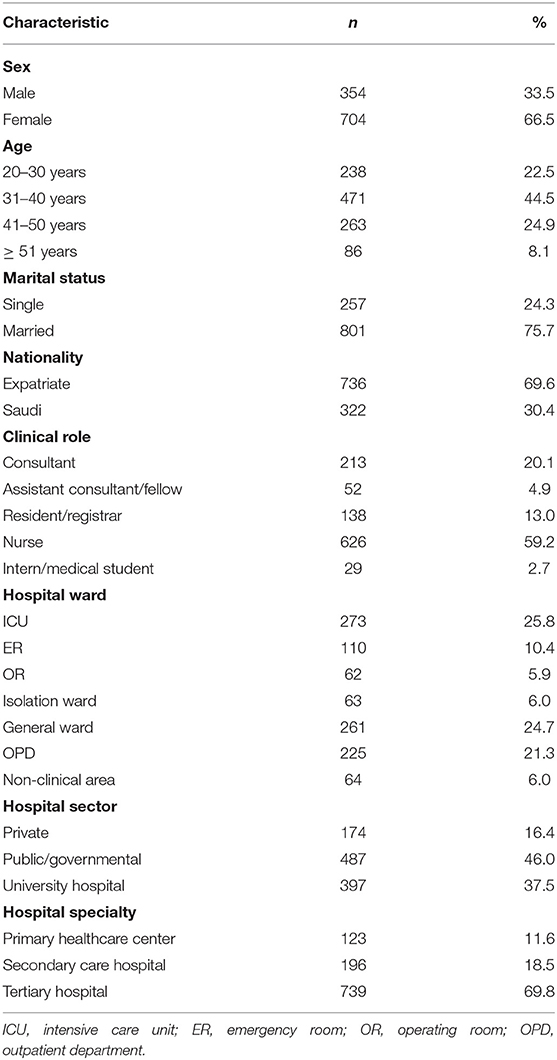

In total, 1,212 HCWs participated in the survey. Of these, 1,058 completed the survey, resulting in a completion rate of 87.2%. Most participants were female (66.5%), between the ages of 31 and 40 years (44.5%) and married (75.7%). Most respondents were nurses (59.2%), followed by physicians (38.0%). Participants worked in intensive care units (ICUs) (25.8%), general wards (24.7%), or outpatient departments (OPDs) (21.3%) in various hospital settings (Table 1).

Table 1. Descriptive analysis of HCWs' sociodemographic and professional characteristics (N = 1,058).

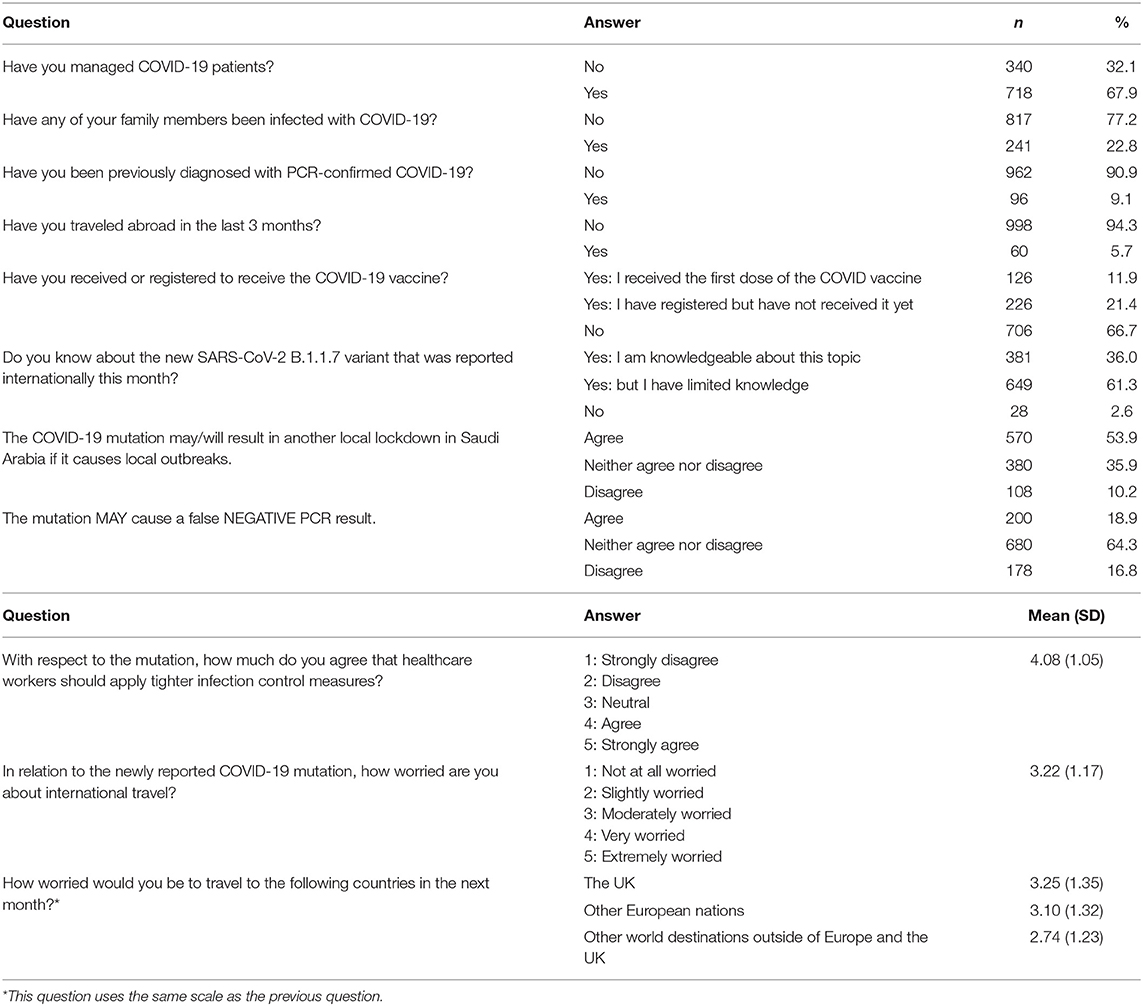

The majority of HCWs (67.9%) reported managing COVID-19 patients. Additionally, 22.8% had encountered an infected family member, and 9.1% reported having been infected with laboratory-confirmed COVID-19 themselves. Only (11.9%) have already received the first dose of the vaccine and another (21.4%) had registered the COVID-19 vaccine. Almost all HCWs reported that they were aware of the B.1.1.7 variant (97.3%), with 36.0% reporting that they had sufficient knowledge of the variant. Although most participants (64.3%) were unsure whether the new mutation could cause a false-negative polymerase chain reaction (PCR) result, 18.9% of them thought it would. Most of the respondents (59.8%) agreed that the management of the new mutation would be similar to the current COVID-19 management guidelines. More than half of the participants (53.9%) believed that the new SARS-CoV-2 mutation outbreak in foreign countries would result in subsequent lockdowns if it reached the KSA. When HCWs were asked to indicate their level of agreement on the need to impose tighter infection control measures due to the new mutation variant, a high level of agreement (M = 4.08 on a scale of 5, SD = 1.05) was found. Regarding worry about international travel within the next month, high levels of worry were found among participants, with the highest levels of the worry associated with travel to the UK (M = 3.25, SD = 1.35), which was slightly higher than their worry levels about traveling abroad generally (M = 3.22, SD = 1.07) (Table 2).

HCWs' Awareness of and Sources of Information About the New COVID-19 Mutation

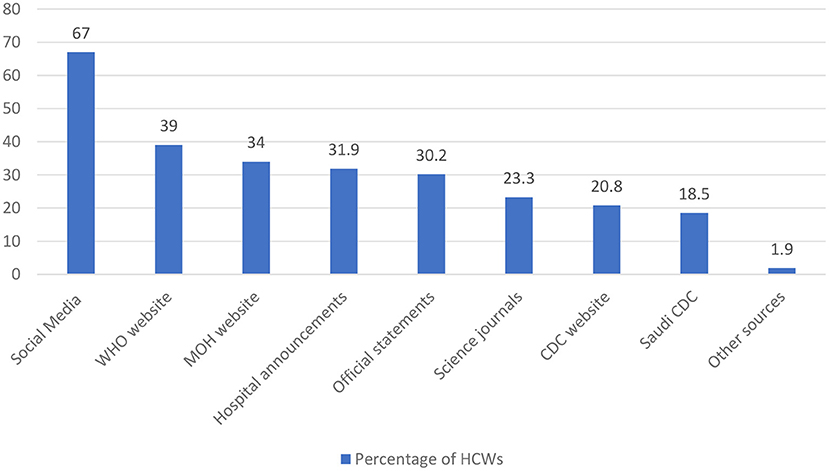

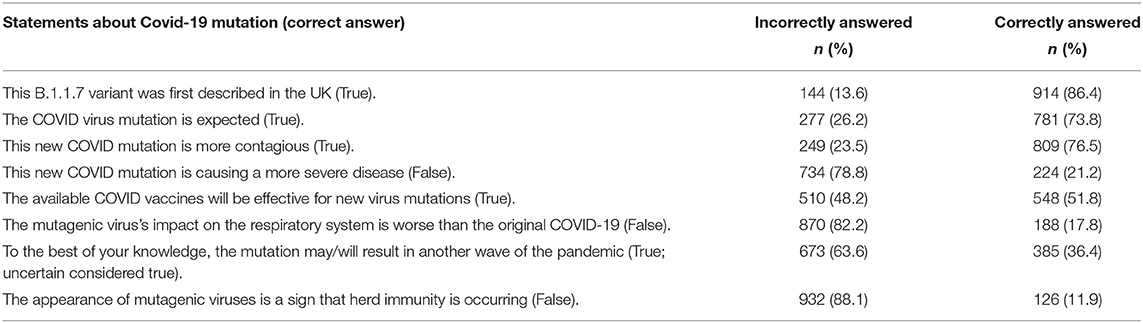

HCWs' sources of information about the mutant variant of COVID-19 are shown in Figure 1. The most common source of information was social media networks (67.0%), followed by the World Health Organization (WHO) website, Saudi Ministry of Health (MOH) website, and hospital or official announcements, while the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) website was only used by 20.8 % of HCWs. HCWs' awareness of and knowledge about the new COVID-19 mutation was measured using eight questions (Table 3). The overall mean awareness score was 3.76 (SD: 1.23) out of 8.00.

Most HCWs (86.4%) were aware that the new variant was first described in the U.K., 73.8% reported that the mutation is an expected evolutionary phenomenon, and 76.5% were aware that it is more contagious. However, the majority of participants believed that the new mutation would cause a more severe disease and likely have a greater negative impact on the respiratory system. In addition, most HCWs thought that the emergence of this mutation was a sign that herd immunity is occurring.

International Travel Worries Among HCWs Due to the Emergence of Mutant COVID-19 Strains

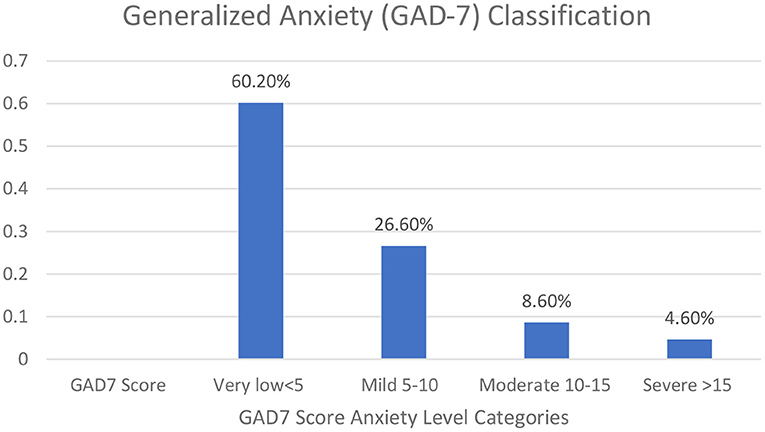

The majority of participants were expatriates living and working in Saudi Arabia. We measured HCWs' worry levels regarding international travel. In addition, we evaluated the degree of HCW anxiety using the General Anxiety Disorder (GAD−7) scale which showed a mean score (SD) of 5 (± 5) for the whole group. Figure 2 showed the distribution of the degree of anxiety among HCWs.

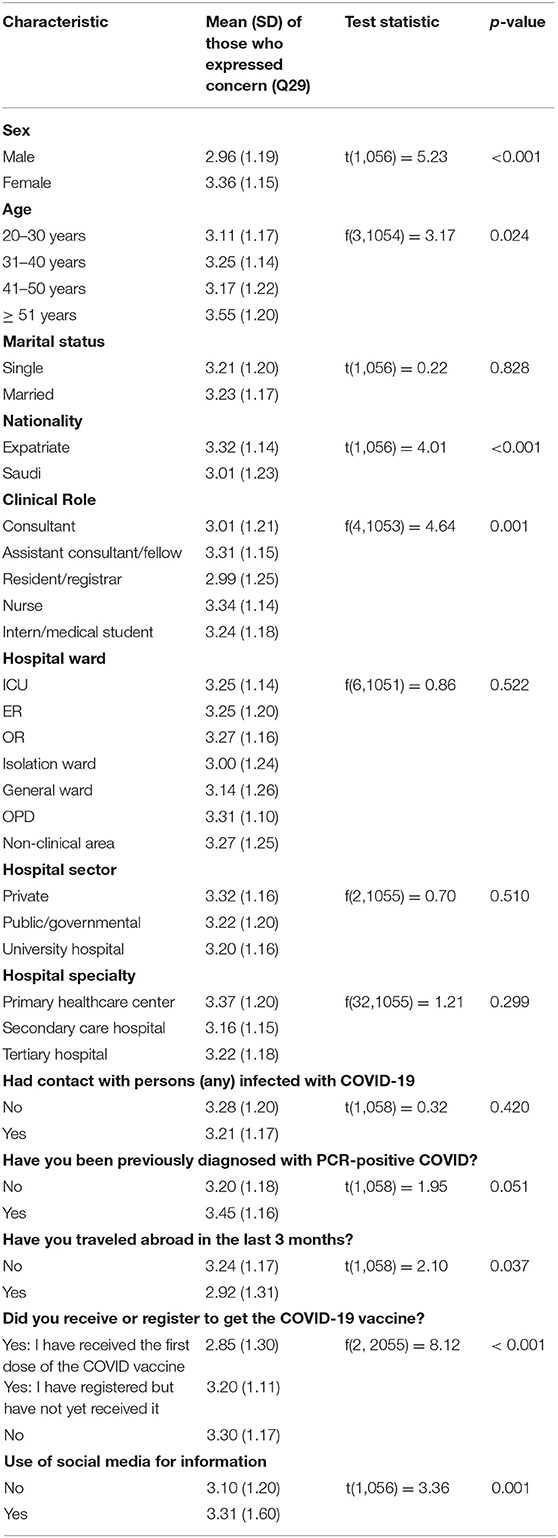

A bivariate analysis was conducted to illustrate the association between HCWs' characteristics and their perceived levels of worry about traveling abroad due to the emergence of the new mutation (Table 4). Female HCWs (mean = 3.36, P < 0.001) and those over 50 years of age (mean = 3.55, P = 0.024) were significantly more worried about international travel than males and HCWs under 50, respectively. In addition, expatriate HCWs had a higher level of worry regarding travel compared to native Saudi HCWs (P < 0.001).

Table 4. Bivariate analysis of HCWs' characteristics and perceived worry regarding traveling abroad due to the emergence of the mutant COVID-19 strain (N = 1,058).

Nurses and interns/medical students were more worried than those assigned to other clinical roles (P = 0.001). Additionally, those who reported they had not traveled in the previous 3 months and those who had not received or registered for the COVID-19 vaccine were also significantly more worried than those who had traveled or received the vaccine (P = 0.037, P < 0.001, respectively). Interestingly, those HCWs who used social media as a source of information were significantly more worried about traveling abroad due to the emergence of the new mutant strain.

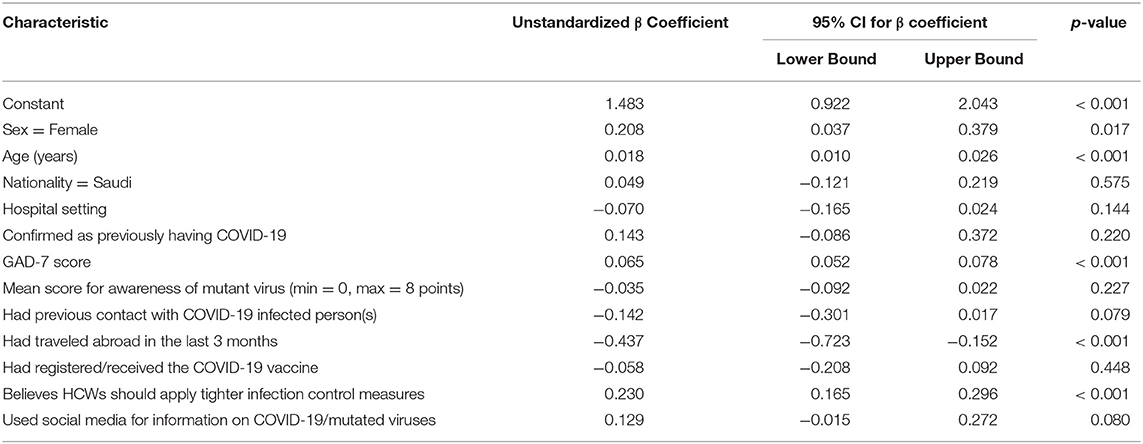

Further, multivariate linear regression analyses (Table 5) were used to predict respondents' characteristics based on their level of worry associated with traveling abroad. This revealed a significant correlation for HCWs' level of travel worry with older age, female sex, higher GAD-7 scores, abstinence from traveling abroad in the previous 3 months, and the belief that HCWs should apply tighter infection control measures due to the emergence of mutant strains. However, no significant correlation was found between HCWs' level of travel worry and their status as having received or registered to receive the vaccine. In addition, the analysis model indicated that people who had traveled abroad recently had a significantly lower mean level of worry regarding international travel outside the UK (β = −0.437, p < 0.001).

Table 5. Multivariate linear regression analysis of HCWs' level of worry regarding traveling abroad (N = 1,058).

Furthermore, a bivariate Pearson's correlation test was conducted and showed that HCWs' worry about international travel correlated significantly and positively with their GAD-7 scores (r = 0.310, p < 0.010) and perceived importance of applying stricter infection control measures (r = 0.256, p < 0.010).

Discussion

In this first reported survey on SARS-CoV-2 B.1.1.7 lineage-related perceptions and travel worry among HCWs, most respondents were aware of the emergence of the variant and had significant anxiety regarding traveling to affected countries, especially to the UK. At the time of our study, there were no published data on B.1.1.7 lineage from the region. Later on, in one study from Jordan, the B.1.1.7 variant was isolated from 36 (6.2%) of studied isolates (15). By Feb 2021, 13 countries in the Middle East reported B.1.1.7 variants (16).

Females and nurses expressed the highest degree of worry about travel, and most of our study participants were nurses (59.0%), with two-thirds being expatriates. Our respondents, therefore, are comparable to the HCWs structure in Saudi Arabia, where physiciansccomprise 36.2 %), and nurses (63.8%) (17). Saudi Arabia's health care system workforce relies heavily on expatriates, specifically female nurses, as only one-third of the nursing workforce is comprised of Saudis (18). That fact shed light on these HCWs being expatriate who usually resides in housing compounds in shared rooms and facilities (19) that can be hazardous in terms of transmission of the disease among themselves and within the health care system, a previous MERS-CoV hospital outbreak in Saudi Arabia was in part related to such accommodations (20). Travel needs could explain why expatriate female nurses, who make up most survey respondents, have such a high degree of concern about international travel, adding to that the fact many of these expatriate HCWs have been stranded abroad during the pandemic due to travel restrictions and the emergence of the variant strain with potential tighter restrictions on traveling to be applied or reapplied in addition to high travel anxiety among those HCW all potentially might endanger our health care system manpower. These findings and previous experiences with MERS-CoV and our findings should alert public health officials to reevaluate their long-term strategy for training and empowering local frontline HCWs.

On the other hand, just recently, HCWs in Saudi Arabia were exempted from the travel bans. In our survey, a few HCWs indicated that they had traveled to countries with potential cases of the new variant in recent months, despite quarantine measures on symptomatic returning travelers. HCWs who return from international travel could pose a potential risk of introducing emerging variants (21). Almost two-thirds of participants had dealt with COVID-19 infected patients, 23.0% had a family member who had been diagnosed with the disease, and about 10.0% had been infected themselves. These results are similar to a previous cross-sectional survey of nearly 1,500 HCWs in Saudi Arabia, which found that 12.8% of HCWs had been infected (13). In that same report, two-thirds of participants were willing to receive an authorized COVID-19 vaccine when available. However, our findings of the actual implementation of the vaccine contradict this as 66% didn't register or receive the vaccine even though of our findings of moderate level of anxiety to travel abroad among surveyed HCWs which should intuitively motivate any person to take the vaccinedespite the vaccine being authorized and available free of charge in Saudi Arabia. These findings should also alert public health officials to introduce targeted vaccine campaigns among HCWs.

Most participants were aware of the new variant reported, with more than one-third indicating confidence in their knowledge. However, only one-fifth were aware that it may cause a false negative PCR result. Recently, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (21) identified three different molecular techniques that may be affected by the variant and recommended that HCWs be aware of the different genetic variants of SARS-CoV-2 that may affect test results depending on the type of molecular test used to diagnose a patient. Of notion, the majority of the real-time PCR Kits used routinely in Saudi Arabia for detection of SARS-CoV-2 do not contain the S gene; thus, the effect of the S gene dropout pattern will not be significant. Negative results should be considered in combination with a clinical evaluation (21).

Our study showed that 86.0% of HCWs were aware that the new variant was first described in the U.K. and that many countries have subsequently reported cases. This highlights the importance of HCWs and infection control authorities keeping up to date about those countries when assessing returning travelers. With the rapidly changing picture of variants circulating in each district or city, this may be different inside each country as well (22).

Regarding the behavior of the mutant strain, most of our HCWs knew that it is more contagious, and they incorrectly expected it to cause a more severe disease than the original strain. The new variant has been reported to be 56% more infectious (23). When asked whether the current COVID-19 vaccine would prevent infection, this was met with uncertainty which might have partially affected their low uptake of the vaccine. It is not yet scientifically proven whether any type of vaccination will be effective in preventing infection from emerging variants. In-vitro studies have shown that the BNT162b2 vaccine neutralizes SARS-CoV-2 viruses carrying N501Y mutations, but more clinical data are still needed (24).

In the current study, 67.0% of the respondents acquired their information from social media. Social media has played an important role in information accuracy as well as spreading misleading information during the COVID-19 pandemic (25). In a previous study from the KSA, 44.1% of participants used a social media platform such as Twitter (25). In our study, 73.0% of the respondents used either the WHO or MOH websites for information. This is an important finding that may direct plans for the dissemination of information about the pandemic.

It is interesting to note that in the bivariate analysis, HCWs' perceived level of travel worry was significantly associated with their use of social media as a source of information. This association may be related to the high degree of fear that tends to be reflected in the media. However, a study from the U.S. found a decreased level of concern about COVID-19 among individuals who used news outlets such as CNN or Fox News as their primary source of information (26).

Other factors that were significantly associated with HCWs' decreased level of travel worry were being male, older age, and being a Saudi national. Several factors have been shown to contribute to people's general levels of anxiety about COVID-19. A review study from China and India that included 18 studies with a total of 79,664 participants showed that the level of stress among the general population regarding COVID-19 was associated with having patient contact and being of the female gender (27). In addition, our study showed increased levels of travel worry among nurses and assistant consultants/fellows; however, it is important to keep in mind that the level of anxiety about COVID-19 is also a factor of time, as one study showed variable anxiety levels as the pandemic has evolved (28). It is expected that individuals who worry about additional lockdowns would also be concerned about travel, as shown by Lee et al. (29). It is interesting to note that in our study, participants who answered that the mutation may cause a false negative PCR result were more worried about travel. The SARS-CoV-2 mutation may or may not result in a false negative PCR result based on the location of the mutation and the molecular test being used (30).

COVID-19 has been associated with significant anxiety among HCWs in Saudi Arabia (12, 31). Our descriptive Pearson's bivariate correlations analysis showed that there was a significant correlation between worry regarding travel, the perceived importance of infection control, and generalized anxiety. This is an important finding, as a previous study found that increased resilience scores is a factor that reduces the rate of anxiety related to COVID-19 (32).

However, despite an overall low to mild GAD-7 scores, we found a link between advanced age and worry regarding travel which seems expected, as older people have more health concerns and are more susceptible to severe forms of infection and a higher fatality rate (33). To add to this, HCWs have a higher risk of catching COVID-19, with an estimated risk of three to 5-fold greater than that of the general population (34). The literature has also shown that older HCWs are more affected by the Pandemic. For example, the median age of HCWs who have died due to COVID-19 in China is 55 years (35). As a result, the U.S. Department of Labor recommends recognizing older age as an individual risk factor and addressing it when planning for pandemics (36). P This background could explain why HCWs in this study recommended applying tighter infection control measures than those currently in place. It also may speak to their recent experiences as frontline workers during the Pandemic, as most of our respondents were registered nurses.

HCWs who had abstained from travel recently were more worried about traveling abroad. Other studies have observed a correlation between threat severity and susceptibility to the virus, which has caused travel fear and resulted in travel restrictions due to the COVID-19 outbreak (37). Studies have reported that similar post-disaster travel behaviors were influenced by risk perceptions and motivations (38, 39).

We used a self-reported anxiety questionnaire (GAD-7) that is designed to assess the participants' mental health status during the previous 2 weeks, which is well-suited to the situation of emerging news about this mutation. The GAD-7 questionnaire inquires about the overall degree to which the respondent has felt nervous, with free-floating anxiety themes (40). A previous study showed that HCWs had a higher prevalence of anxiety at baseline prior to the Pandemic (41). Similarly, numerous national studies have reported an increased level of anxiety symptoms in HCWs during the COVID-19 Pandemic (42–44). To understand this finding, we hypothesize our study likely included HCWs with high baseline anxiety levels, whose anxiety levels are now increased even more due to the SARS-CoV-2 new mutation.

HCWs' travel worries due to the new SARS-CoV-2 genetic variants should be addressed, especially because HCWs are more prone to developing mental health problems such as anxiety, depression, and substance abuse during pandemics (45, 46). Therefore, screening and supporting expatriate or traveling HCWs could improve their mental well-being, as well as advising against HCWs' travel except for “really needed” until the pandemic crisis is over.

Study Limitations and Strengths

This work is among the first research projects to explore travel worries among HCWs regarding the travel worries and restrictions caused by new genetic variants of the SARS-CoV-2 virus. However, there are some limitations to this study. We have used convenience sampling, potentially limiting the representation of the study's sample. Responses were predominantly from COVID-19 frontline physicians and nurses that did not include some categories of HCWs, such as dentists and laboratory workers, which resulted in possible selection bias. We have used an online questionnaire, potentially introducing voluntary response and non-response bias since motivated and internet literate respondents would complete the survey. This could further reduce the generalizability of our findings.

However, our sampling technique and the cross-sectional design are employed based on the study's objective during the ongoing Pandemic. For our study, it was to quickly collect data to generate hypotheses, signifying that convenience sampling would be satisfactory. This is especially important with the limited published studies on travel worries among HCWs regarding the travel restrictions caused by new genetic variants of the SARS-CoV-2 virus. Nevertheless, the study findings, including associations, should be interpreted with caution. We believe that potential future research would build on our findings with other approaches to data collection and sampling techniques to ensure a more representative sample.

Conclusion

Most HCWs were aware of the emergence of the SARS-CoV-2 B.1.1.7 variant and expressed substantial travel worries in relation to it. The levels of travel worries were greater among expatriate, female nurse HCWs, those who used social media as their main source of information, who had not registered for the COVID-19 vaccine, and who had high GAD-7 scores. Such high levels of worry, especially among expatriate HCWs, need to be addressed urgently in order to maintain our workforce capacity to keep facing the ongoing Pandemic. In addition, public health authorities' utilization of official social media platforms could improve the dissemination of accurate information among HCWs regarding the virus's evolving mutations. Targeted vaccine campaigns are warranted primarily to ensure HCWs uptake of the vaccine being the frontline in the current Pandemic and to make them aware of the efficacy of COVID-19 vaccines toward the genetic variants of SARS-CoV-2.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Ethics Statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by IRB, King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. Written informed consent for participation was not required for this study in accordance with the national legislation and the institutional requirements.

Author Contributions

M-HT, MB, JA-T, FAlj, ANA, AA-E, and RH conceptualized the study, analyzed the data, and wrote the manuscript. BS, FAls, AAlh, KA, AAla, SA, and RT contributed to the study design, collected, analyzed, and interpreted data, and edited the manuscript. NA contribution to the study design and interpretation and edited the manuscript. FAlz, AJ, and SE interpreted the data and finalized the manuscript. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding

This study was supported by King Saud University, Deanship of Scientific Research, Research Chair for Evidence-Based Health Care and Knowledge. The research team is thankful for the statistical data analysis consultation offered by www.hodhodata.com.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

CDC, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; COVID-19, Coronavirus disease 2019; GAD-7, Generalized Anxiety Disorder Assessment; SARS-CoV-2, Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2; WHO, World Health Organization.

References

1. CDC. Emerging SARS-CoV-2 Variants. Available online at: https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/more/science-and-research/scientific-brief-emerging-variants.html (accessed January 14, 2021).

2. Wise J. Covid-19: new coronavirus variant is identified in UK. BMJ. (2020) 371:m4857. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m4857

4. ECDC. Risk Related to Spread of New SARSCoV-2 Variants of Concern in the EU/EEA. Available online at: https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/sites/default/files/documents/COVID-19-risk-related-to-spread-of-new-SARS-CoV-2-variants-EU-EEA.pdf (accessed January 14, 2021).

5. CDC. New COVID-19 Variants. Available online at: https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/transmission/variant.html (accessed January 14, 2021).

6. Al-Tawfiq JA, Memish ZA. COVID-19 in the eastern mediterranean region and saudi arabia: prevention and therapeutic strategies. Int J Antimicrob Agents. (2020) 55:105968. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2020.105968

7. Al-Hanawi MK, Khan SA, Al-Borie HM. Healthcare human resource development in saudi arabia: emerging challenges and opportunities-a critical review. Public Health Revi. (2019) 40:1–1. doi: 10.1186/s40985-019-0112-4

8. Gassem L. Flight Rush to Saudi Arabia as Travel Ban Lifted. (2021). Available online at: https://www.arabnews.com/node/1786871/saudi-arabia (accessed January 16, 2021).

9. Tselebis A, Gournas G, Tzitzanidou G, Panagiotou A, Ilias I. Anxiety and depression in Greek nursing and medical personnel. Psychol Rep. (2006) 99:93–6. doi: 10.2466/PR0.99.5.93-96

10. SPA. Saudi Food and Drug Authority (SFDA) Approves Registration of Pfizer-BioNTech COVID-19 Vaccine. (2020). Available online at: https://www.spa.gov.sa/viewfullstory.php?lang=en&newsid=2166947 (accessed January 18, 2021).

11. Temsah MH, Alhuzaimi AN, Alamro N, Alrabiaah A, Al-Sohime F, Alhasan K, et al. Knowledge, attitudes, and practices of healthcare workers during the early COVID-19 pandemic in a main, academic tertiary care centre in saudi arabia. Epidemiol Infect. (2020) 148:1–29. doi: 10.1017/S0950268820001958

12. Temsah MH, Al-Sohime F, Alamro N, Al-Eyadhy A, Al-Hasan K, Jamal A, et al. The psychological impact of COVID-19 pandemic on health care workers in a MERS-CoV endemic country. J Infect Public Health. (2020) 13:877–82. doi: 10.1016/j.jiph.2020.05.021

13. Barry M, Temsah M-H, Alhuzaimi A, Alamro N, Al-Eyadhy A, Aljamaan F, et al. COVID-19 vaccine confidence and hesitancy among healthcare workers: a cross-sectional survey from a MERS-CoV experienced nation. Medrxiv [preprint]. (2020) 1–24. doi: 10.1101/2020.12.09.20246447

14. Xiaoming X, Ming A, Su H, Wo W, Jianmei C, Qi Z, et al. The psychological status of 8817 hospital workers during COVID-19 epidemic: a cross-sectional study in chongqing. J Affect Disord. (2020) 276:555–61. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2020.07.092

15. Sallam M, Mahafzah A. Molecular analysis of SARS-CoV-2 genetic lineages in jordan: tracking the introduction and spread of COVID-19 UK variant of concern at a country level. Pathogens. (2021) 10:302. doi: 10.3390/pathogens10030302

16. W EMRO. COVID-19: WHO EMRO Biweekly Situation Report #4. Available online at: http://www.emro.who.int/images/stories/coronavirus/documents/covid_19_bi_weekly_sitrep-four.pdf?ua=1 (accessed April 21, 2021).

17. Alwatan. 494 Hospitals in the Kingdom Provide One Bed For Every 446 People. (2020). Available online at: https://www.alwatan.com.sa/article/1042788# (accessed April 21, 2021).

18. Almalki M, Fitzgerald G, Clark M. Health care system in Saudi Arabia: an overview. East Mediterr Health J. (2011) 17:784–93. doi: 10.26719/2011.17.10.784

19. Aldossary A, While A, Barriball L. Health care and nursing in Saudi Arabia. Int Nurs Rev. (2008) 55:125–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1466-7657.2007.00596.x

20. Barry M, Phan MV, Akkielah L, Al-Majed F, Alhetheel A, Somily A, et al. Nosocomial outbreak of the middle east respiratory syndrome coronavirus: a phylogenetic, epidemiological, clinical and infection control analysis. Travel Med Infect Dis. (2020) 37:101807. doi: 10.1016/j.tmaid.2020.101807

21. FDA. Genetic Variants of SARS-CoV-2 May Lead to False Negative Results with Molecular Tests for Detection of SARS-CoV-2 - Letter to Clinical Laboratory Staff and Health Care Providers. (2021). Available online at: https://www.fda.gov/medical-devices/letters-health-care-providers/genetic-variants-sars-cov-2-may-lead-false-negative-results-molecular-tests-detection-sars-cov-2 (accessed January 16, 2021).

22. CDC. Variant Proportions in the U.S. (2021). Available online at: https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/cases-updates/variant-proportions.html (accessed March 28, 2021).

23. Davies NG, Barnard RC, Jarvis CI, Kucharski AJ, Munday J, Pearson CA, et al. Estimated transmissibility and severity of novel SARS-CoV-2 Variant of Concern 202012/01 in England. Medrxiv. (2020) 372:eabg3055. doi: 10.1126/science.abg3055

24. Xie X, Zou J, Fontes-Garfias CR, Xia H, Swanson KA, Cutler M, et al. Neutralization of N501Y mutant SARS-CoV-2 by BNT162b2 vaccine-elicited sera. Biorxiv [preprint]. (2021) 1–6. doi: 10.1101/2021.01.07.425740

25. Alnasser AHA, Al-Tawfiq JA, Al Kalif MSH, Alobaysi AMA, Al Mubarak MHM, Alturki HNH, et al. The positive impact of social media on the level of COVID-19 awareness in Saudi Arabia: a web-based cross-sectional survey. Infez Med. (2020) 28:545–550.

26. van Stekelenburg A, Schaap G, Veling H, Buijzen M. Investigating and improving the accuracy of US citizens' beliefs about the COVID-19 pandemic: longitudinal survey study. J Med Internet Res. (2021) 23:e24069. doi: 10.2196/24069

27. Gilan D, Röthke N, Blessin M, Kunzler A, Stoffers-Winterling J, Müssig M, et al. Psychomorbidity, resilience, and exacerbating and protective factors during the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic. Dtsch Arztebl Int. (2020) 117:625–30. doi: 10.3238/arztebl.2020.0625

28. Temsah M-H, Alhuzaimi AN, Alrabiaah A, Alamro N, Alsohime F, Al-Eyadhy A, et al. Changes in healthcare workers' knowledge, attitudes, practices, and stress during the COVID-19 pandemic. Medicine (Baltimore). (2021) 100:e25825. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000025825

29. Lee H, Noh EB, Choi SH, Zhao B, Nam EW. Determining public opinion of the COVID-19 pandemic in South Korea and Japan: social network mining on twitter. Healthc Inform Res. (2020) 26:335–43. doi: 10.4258/hir.2020.26.4.335

30. Young K. FDA Warns of False Negative COVID Tests From Virus Mutations. (2021). Available online at: https://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/943845#:~:text=The%20US%20Food%20and%20Drug,genome%20assessed%20by%20that%20test (accessed January 16, 2021).

31. Abolfotouh MA, Almutairi AF, BaniMustafa AA, Hussein MA. Perception and attitude of healthcare workers in Saudi Arabia with regard to Covid-19 pandemic and potential associated predictors. BMC Infect Dis. (2020) 20:719. doi: 10.1186/s12879-020-05443-3

32. Carriedo A, Cecchini JA, Fernández-Río J, Méndez-Giménez A. Resilience and physical activity in people under home isolation due to COVID-19: A preliminary evaluation. Ment Health Phys Act. (2020) 19:100361. doi: 10.1016/j.mhpa.2020.100361

33. Mendes A, Serratrice C, Herrmann FR, Genton L, Périvier S, Scheffler M, et al. Predictors of in-hospital mortality in older patients with COVID-19: the COVIDAge study. J Am Med Dir Assoc. (2020) 21:1546–54.e3. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2020.09.014

34. Nguyen LH, Drew DA, Graham MS, Joshi AD, Guo CG, Ma W, et al. Risk of COVID-19 among frontline health-care workers and the general community: a prospective cohort study. Lancet Public Health. (2020) 5:e475–83. doi: 10.1016/S2468-2667(20)30164-X

35. Zhan M, Qin Y, Xue X, Zhu S. Death from Covid-19 of 23 health care workers in China. N Engl J Med. (2020) 382:2267–8. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2005696

36. OSHA. Guidance on Preparing Workplaces for COVID-19. (2020). Available online at: https://www.osha.gov/Publications/OSHA3990.pdf (accessed January 18, 2021).

37. Zheng D, Luo Q, Ritchie BW. Afraid to travel after COVID-19? Self-protection, coping and resilience against pandemic ‘travel fear’. Tour Manag. (2021) 83:104261. doi: 10.1016/j.tourman.2020.104261

38. Biran A, Liu W, Li G, Eichhorn V. Consuming post-disaster destinations: The case of Sichuan, China. Ann Tour Res. (2014) 47:1–17. doi: 10.1016/j.annals.2014.03.004

39. Su Y, Zhao F, Tan L. Whether a large disaster could change public concern and risk perception: a case study of the 7/21 extraordinary rainstorm disaster in Beijing in 2012. Nat Hazards. (2015) 78:555–67. doi: 10.1007/s11069-015-1730-x

40. Tiirikainen K, Haravuori H, Ranta K, Kaltiala-Heino R, Marttunen M. Psychometric properties of the 7-item generalized anxiety disorder scale (GAD-7) in a large representative sample of Finnish adolescents. Psychiatry Res. (2019) 272:30–35. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2018.12.004

41. Weaver MD, Vetter C, Rajaratnam SMW, O'Brien CS, Qadri S, Benca RM, et al. Sleep disorders, depression and anxiety are associated with adverse safety outcomes in healthcare workers: a prospective cohort study. J Sleep Res. (2018) 27:e12722. doi: 10.1111/jsr.12722

42. Gupta AK, Mehra A, Niraula A, Kafle K, Deo SP, Singh B, et al. Prevalence of anxiety and depression among the healthcare workers in Nepal during the COVID-19 pandemic. Asian J Psychiatr. (2020) 54:102260. doi: 10.1016/j.ajp.2020.102260

43. Wilson W, Raj JP, Rao S, Ghiya M, Nedungalaparambil NM, Mundra H, et al. Prevalence and predictors of stress, anxiety, and depression among healthcare workers managing COVID-19 pandemic in India: a nationwide observational study. Ind J Psychol Med. (2020) 42:353–8. doi: 10.1177/0253717620933992

44. Pappa S, Ntella V, Giannakas T, Giannakoulis VG, Papoutsi E, Katsaounou P. Prevalence of depression, anxiety, and insomnia among healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Brain Behav Immunity. (2020) 1–26. doi: 10.2139/ssrn.3594632

45. Temsah M-H, Alenezi S. Understanding the psychological stress and optimizing the psychological support for the acute-care health-care workers during the COVID-19 pandemic. Saudi Crit Care J. (2020) 4:25. doi: 10.4103/sccj.sccj_62_20

Keywords: COVID-19 vaccine, B.1.1.7 variant, heathcare workers perception, travel worry, COVID-19 vaccine acceptance, UK variant of concern

Citation: Temsah M-H, Barry M, Aljamaan F, Alhuzaimi AN, Al-Eyadhy A, Saddik B, Alsohime F, Alhaboob A, Alhasan K, Alaraj A, Halwani R, Jamal A, Alamro N, Temsah R, Esmaeil S, Alenezi S, Alzamil F, Somily AM and Al-Tawfiq JA (2021) SARS-CoV-2 B.1.1.7 UK Variant of Concern Lineage-Related Perceptions, COVID-19 Vaccine Acceptance and Travel Worry Among Healthcare Workers. Front. Public Health 9:686958. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2021.686958

Received: 29 March 2021; Accepted: 28 April 2021;

Published: 26 May 2021.

Edited by:

Kin On Kwok, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, ChinaReviewed by:

Malik Sallam, The University of Jordan, JordanQi Wang, The University of Hong Kong, China

Copyright © 2021 Temsah, Barry, Aljamaan, Alhuzaimi, Al-Eyadhy, Saddik, Alsohime, Alhaboob, Alhasan, Alaraj, Halwani, Jamal, Alamro, Temsah, Esmaeil, Alenezi, Alzamil, Somily and Al-Tawfiq. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Amr Jamal, amrjamal@ksu.edu.sa; med.researcher.2020@gmail.com

†These authors have contributed equally to this work

‡ORCID: Mohamad-Hani Temsah orcid.org/0000-0002-4389-9322

Mazin Barry orcid.org/0000-0003-2274-007X

Fadi Aljamaan orcid.org/0000-0001-8404-6652

Abdullah N. Alhuzaimi orcid.org/0000-0002-9380-079X

Ayman Al-Eyadhy orcid.org/0000-0002-6051-9125

Basema Saddik orcid.org/0000-0002-4682-5927

Fahad Alsohime orcid.org/0000-0002-4979-3895

Ali Alhaboob orcid.org/0000-0003-2126-7874

Khalid Alhasan orcid.org/0000-0002-4291-8536

Ali Alaraj orcid.org/0000-0002-7706-2328

Amr Jamal orcid.org/0000-0002-4051-6592

Nurah Alamro orcid.org/0000-0001-9489-3994

Samia Esmaeil orcid.org/0000-0001-9173-2669

Shuliweeh Alenezi orcid.org/0000-0002-7049-0960

Jaffar A. Al-Tawfiq orcid.org/0000-0002-5752-2235

Mohamad-Hani Temsah1†‡

Mohamad-Hani Temsah1†‡ Mazin Barry

Mazin Barry Fadi Aljamaan

Fadi Aljamaan Ayman Al-Eyadhy

Ayman Al-Eyadhy Basema Saddik

Basema Saddik Khalid Alhasan

Khalid Alhasan Rabih Halwani

Rabih Halwani Amr Jamal

Amr Jamal Nurah Alamro

Nurah Alamro Reem Temsah

Reem Temsah Shuliweeh Alenezi

Shuliweeh Alenezi Ali M. Somily

Ali M. Somily Jaffar A. Al-Tawfiq

Jaffar A. Al-Tawfiq