Abstract

Background: In this study, we developed cost prediction equations that facilitate estimation of the costs of various cardiovascular events for patients of specific demographic and clinical characteristics over varying time horizons.

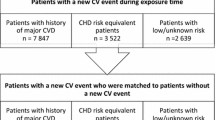

Methods: We used administrative claims data and generalized linear models to develop cost prediction equations for selected cardiovascular events, including myocardial infarction (MI), angina, strokes and revascularization procedures. Separate equations were estimated for patients with events and for their propensity score-matched controls. Attributable costs were estimated on a monthly basis for the first 36 months after each event and annually thereafter, with differences in survival between cases and controls factored into the longitudinal cost calculations. The regression models were used to estimate event costs ($US, year 2007 values) for the average patient in each event group, over various time periods ranging from 1 month to lifetime.

Results: When the equations are run for the average patient in each event group, attributable costs of each event in the acute phase (i.e. first 3 years) are substantial (e.g. MI $US73 300; hospitalization for angina $US36 000; nonfatal haemorrhagic stroke $US71 600). Furthermore, for most events, cumulative costs remain substantially higher among cases than among controls over the remaining lifetime of the patients.

Conclusions: This study provides updated estimates of medical care costs of cardiovascular events among a managed care population over various time horizons. Results suggest that the economic burden of cardiovascular disease is substantial, both in the acute phase as well as over the longer term.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Framingham Heart Study. A project of the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute and Boston University [online]. Available from URL: http://www.framinghamheartstudy.org [Accessed 2008 Nov 1]

Anderson KM, Odell PM, Wilson PWF, et al. Cardiovascular disease profiles. Am Heart J 1990; 121: 293–8

Anderson KM, Wilson PWF, Odell PM, et al. An updated coronary risk profile: a statement for health professionals. Circulation 1991; 83 (1): 356–62

D’Agostino RB, Russell MW, Huse DM, et al. Primary and subsequent coronary risk appraisal: new results from the Framingham Heart Study. Am Heart J 2000 Feb; 139: 272–81

Weinstein MC, Coxson PG, Williams LW, et al. Forecasting coronary heart disease incidence, mortality, and cost: the Coronary Heart Disease Policy Model. Am J Public Health 1987; 77: 1417–26

Grover SA, Abrahamowicz M, Joseph L, et al. The benefits of treating hypercholesterolemia to prevent coronary heart disease: estimating changes in life expectancy and morbidity. JAMA 1992; 267: 816–22

Babad H, Sanderson C, Naidoo B, et al. The development of a simulation model of primary prevention strategies for coronary heart disease. Health Care Manag Sci 2002; 5: 269–74

Cooper K, Davies R, Roderick P, et al. The development of a simulation model of the treatment of coronary heart disease. Health Care Manag Sci 2002; 5: 259–67

Birnbaum H, Leong S, Kabra A. Lifetime medical costs for women: cardiovascular disease, diabetes, and stress urinary incontinence. Womens Health Issues 2003; 13 (6): 204–13

Russell MW, Huse DM, Drowns S, et al. Direct medical costs of coronary artery disease in the US. Am J Cardiol 1998; 81: 1110–5

Taylor TN, Davis PH, Torner JC, et al. Lifetime cost of stroke in the US. Stroke 1996; 27: 1459–66

Lee WC, Christensen MC, Joshi AV, et al. Long-term costs of stroke subtypes among Medicare beneficiaries. Cerebrovasc Dis 2007; 23: 57–65

Mark DB, Knight JD, Cowper PA, et al. Long-term economic outcomes associated with intensive versus moderate lipid-lowering therapy in coronary artery disease: results from the Treating New Targets (TNT) trial. Am Heart J 2008; 156: 698–705

Miller PS, Smith DG, Jones P. Cost effectiveness of rosuvastatin in treating patients to low-density lipoprotein cholesterol goals compared with atorvastatin, pravastatin, and simvastatin (a US Analysis of the STELLAR Trial). Am J Cardiol 2005; 95: 1314–9

Taylor DC, Pandya A, Thompson D, et al. Cost-effectiveness of intensive atorvastatin therapy in secondary cardiovascular prevention in the United Kingdom, Spain, and Germany, based on the Treating New Targets Study. Eur J Health Econ 2009 Jul; 10: 255–65

Ramsey SD, Clarke LD, Roberts CS, et al. An economic evaluation of atorvastatin for primary prevention of cardiovascular events in type 2 diabetes. Pharmacoeconomics 2008; 26: 329–39

Hartunian NS, Smart CN, Thompson MS. The incidence and economic costs of cancer,motor vehicle injuries, coronary heart disease, and stroke: a comparative analysis. Am J Public Health 1980; 70: 1249–60

Dennis MS, Burn JPS, Sandercock PAG, et al. Long-term survival after first-ever stroke: the Oxfordshire Community Stroke Project. Stroke 1993; 24: 796–800

Lampe FC, Whincup PH, Wannamethee SG, et al. The natural history of prevalent ischaemic heart disease in middle-aged men. Eur Heart J 2000; 21: 1052–62

Mosterd A, Cost B, Hoes AW, et al. The prognosis of heart failure in the general population. Eur Heart J 2001; 22: 1318–27

Rosenbaum P, Rubin D. The central role of the propensity score in observational studies for causal effects. Biometrika 1993; 70: 41–55

D’Agostino Jr RB. Tutorial in biostatistics: propensity score methods for bias reduction in comparison of a treatment to a non-randomized control group. Stat Med 1998; 17: 2265–81

Coca-Perraillon M. Local and global optimal propensity score matching [paper 185-2007]. SAS Global Forum, 2007 [online]. Available from URL: http://www.biostat.umn.edu/~will/6470stuff/Class25-10/SAS%20matching%202007.pdf [Accessed 2011 Mar 24]

Mullahy J. Much ado about two: reconsidering retransformation and two-part models in health econometrics. J Health Econ 1998; 17: 247–81

Buntin MB, Zaslavsky AM. Too much ado about twopart models and transformation? Comparing methods of modeling Medicare expenditures. J Health Econ 2004; 23: 525–42

Kruse M, Davidsen M, Madsen M, et al. Costs of heart disease and risk behaviour: implications for expenditure on prevention. Scand J Public Health 2008; 36: 850–6

Acknowledgements

This study was sponsored by Pfizer Inc. Amy O’Sullivan, Jaime Rubin, Joshua Nyambose and David Thompson were employees of i3 Innovus, Medford, MA, USA at the time this research was conducted; i3 Innovus was a paid consultant to Pfizer Inc in connection with the development of the manuscript. David Cohen and Eric Peterson were paid consultants to Pfizer Inc in connection with the development of this manuscript. Andreas Kuznik is a full-time employee of Pfizer Inc. The authors would like to thank Eric Peterson for his contributions to this study. David Cohen has received consulting fees or speaking honoraria from Eli Lilly, Daiichi Sankyo, Medtronic, Cordis, Volcano and St. Jude Medical. He currently receives research grant support from Boston Scientific, Abbott Vascular, Medtronic, Edwards Lifesciences, Astra Zeneca and Medrad.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Electronic supplementary material

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

O’Sullivan, A.K., Rubin, J., Nyambose, J. et al. Cost Estimation of Cardiovascular Disease Events in the US. Pharmacoeconomics 29, 693–704 (2011). https://doi.org/10.2165/11584620-000000000-00000

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.2165/11584620-000000000-00000