Abstract

Despite well-established protocols for the medical management of Von Hippel–Lindau disease (VHL), families affected by this rare tumour syndrome continue to face numerous psychological, social, and practical challenges. To our knowledge, this is one of the first qualitative studies to explore the psychosocial difficulties experienced by families affected by VHL. A semi-structured interview was developed to explore patients’ and carers’ experiences of VHL along several life domains, including: self-identity and self-esteem, interpersonal relationships, education and career opportunities, family communication, physical health and emotional well-being, and supportive care needs. Quantitative measures were also used to examine the prevalence of anxiety, depression, and disease-specific distress in this sample. Participants were recruited via the Hereditary Cancer Clinic at the Prince of Wales Hospital in Sydney, Australia. A total of 23 individual telephone interviews were conducted (15 patients, 8 carers), yielding a response rate of 75%. A diverse range of experiences were reported, including: sustained uncertainty about future tumour development, frustration regarding the need for lifelong medical screening, strained family relationships, difficulties communicating with others about VHL, perceived social isolation and limited career opportunities, financial and care-giving burdens, complex decisions in relation to childbearing, and difficulties accessing expert medical and psychosocial care. Participants also provided examples of psychological growth and resilience, and voiced support for continued efforts to improve supportive care services. More sophisticated systems for connecting VHL patients and their families with holistic, empathic, and person-centred medical and psychosocial care are urgently needed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Von Hippel–Lindau disease (VHL) is a rare, autosomal dominant, early-onset genetic condition with an incidence of approximately 1 in 36 000.1 In almost all cases, the condition is caused by highly penetrant germline mutations in the VHL tumour suppressor gene located on chromosome 3p25–26.2 The condition is characterised by the development of a variety of benign or malignant tumours and cysts, most commonly affecting the brain, spinal cord, retina, kidneys, pancreas, and adrenal glands. The most typical manifestations of VHL are cerebellar haemangioblastomas, retinal haemangiomas, and renal cell carcinomas; the cumulative risk of developing these by age 60 years is 84%, 70%, and 69%, respectively.3, 4 It follows that the majority of people living with VHL will develop one, if not many tumours throughout their life, with clinically relevant symptoms occurring in at least 90% of people with a VHL mutation.3 The mean age at diagnosis of tumours is 26 years (range 4–68 years), and the median life expectancy is estimated to be 59.4 years.5

Screening for tumours associated with VHL is complex and involves multidisciplinary care and the monitoring of multiple organ systems over a lifetime (see Table 1). Screening may commence in children as young as 2 years of age and early diagnosis and treatment may improve prognosis and quality of life.6 Within the same family, individual family members may show one or several features of the disease. Consequently, there is a great deal of unpredictability regarding how and when the disease will manifest across family members. Lifelong commitment to various medical screening regimens may generate diverse emotional responses, including denial, anger, fear, sadness and anxiety, and may influence one’s sense of self, particularly for children, adolescents, and young people.7 The ways in which patients think and feel about VHL, and the meaning of lifelong surveillance, may inevitably influence their ability to accept and practice behaviours that promote health and well-being.8, 9

The rarity of VHL means that there is a paucity of research examining the psychosocial experiences of people affected by the disease. Lammens et al10 recently carried out a cross-sectional study and found that almost 50% of VHL mutation carriers and a third of non-carriers reported clinically relevant levels of disease-related distress. Factors associated with greater distress included participants’ perceived risk of future tumour development, high social constraints (ie, the perceived need to inhibit oneself from sharing thoughts and feelings about VHL with others), and having a family member die at a young age because of VHL. A significant subset of partners (36%) also reported moderate to high levels of VHL-related distress.11 Results such as these call for greater attention and care to be paid to the lived experiences of individuals affected by VHL, so that the factors contributing to high levels of distress can be understood and addressed. The aim of the present study was thus to explore both patients’ and carers’ lived experiences in relation to VHL. Individuals’ beliefs and perceptions of VHL were examined, with a particular focus on the psychological and social implications of the condition for individuals and their families, as well as the supportive care needs of people affected by this disease. Given the paucity of research in this domain, a mixed methods design incorporating a qualitative methodology was considered the most appropriate.12

Materials and Methods

Participants

Participants were recruited via the Hereditary Cancer Clinic (HCC) at the Prince of Wales Hospital in Sydney, Australia. The HCC is one of the largest referral and clinical management centres for VHL in Australia, receiving local, state, national, and regional international referrals. Patients managed locally (53% of participants in this study) have access to psychosocial support from the centre’s genetic counsellors and clinical psychologist. Individuals aged over 18 years with a clinical (based on symptom presentation) or genetic (based on genetic test results) diagnosis of VHL, and their self-identified carers, were eligible for study participation provided they had sufficient English language skills to take part without the aid of an interpreter. Carers were unaffected (non-carrier) relatives or partners defined as ‘someone who provides you with emotional and/or practical support in coping with VHL’.

Recruitment strategy

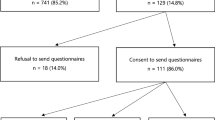

To ensure heterogeneity and to ascertain the full range of beliefs and experiences from as many perspectives as possible, purposive sampling was used.13 An attempt was also made to invite individuals from a range of different age groups, so as to capture potential differences in experiences according to life stage. A letter of invitation was sent to eligible individuals via their treating clinical geneticist, accompanied by a study information sheet, consent form, questionnaire, and reply-paid envelope. Individuals who opted into the study by returning the self-administered questionnaire were then contacted by one of the investigators to arrange a telephone interview. At the end of each interview, participants with VHL were asked to identify a person who they considered to have a care-giving role in their daily life. The appropriate Institutional Review Board (IRB) gave approval and informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Data collection

All semi-structured, individual telephone interviews were recorded and transcribed verbatim. An aide-memoire was specifically designed to scaffold discussions, although the wording and sequencing of questions was left open. A carefully designed suite of questions was used to explore a range of topics, including: beliefs about and experiences of VHL; perceptions of personal susceptibility to tumours; perceived impact of VHL on one’s physical health, emotional well-being, interpersonal relationships, finances, career opportunities, and sense of self; family dynamics and communication about VHL; and information and supportive care needs.

On the basis of a systematic review of the literature and expert consultation, a self-administered survey instrument combining validated and purposely designed scales was also developed. Data were collected as part of a larger study and only responses directly related to psychological adjustment are reported here:

-

1)

Demographics: Age, gender, country of residence, marital status, highest educational attainment, and number and age of children were assessed via standard items.

-

2)

Traumatic stress relating to VHL: Participants rated the frequency of intrusive and avoidant thoughts and behaviours associated with VHL using the 15-item Impact of Events Scale (IES).14 A total score ≥40 was considered indicative of a significant stress response.14, 15 Internal consistency for the IES total score was 0.89.

-

3)

General anxiety and depression: The 14-item Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) was used to measure anxiety and depression.16 Subscale scores ≥8 indicated potentially elevated distress.16 Internal consistency was 0.93 and 0.82 for the anxiety and depression subscales, respectively.

-

4)

Coping: The Brief COPE (28 items)17 was used to assess individuals’ coping responses across behavioural and emotional domains. Each item was rated on a 4-point scale, from 1 (‘I haven’t been doing this at all’) to 4 (‘I have been doing this a lot’).

-

5)

VHL-related clinical characteristics and screening practices: Participants were asked about their (or their family member’s) diagnosis, genetic testing, current tumours, family history of disease and VHL-related deaths, and screening practices (14 items). Beliefs about and barriers to screening (eg, ‘I do not believe that screening applies to me’) were assessed via 16 items, with response options ranging from 1 (‘Strongly agree’) to 5 (‘Strongly disagree’).

-

6)

Carer burden: Carers also completed the 12-item Carer Burden Scale,18 with scores >17 indicating significant caregiving-related burden.18 Internal consistency of the scale was 0.87.

-

7)

Preferred format for receiving VHL-related information: A list of 11 possible patient education resources were presented with a standard definition (see Figure 1). Participants indicated how useful they believed each resource would be from 1 (‘Not at all useful’) to 5 (‘Extremely useful’).

Data analysis

Interview transcripts were analysed in accordance with the conceptual framework of Miles and Huberman.12 This involved an analytic process comprised of four phases: (1) three authors (NK, SM, and AR) independently read four randomly selected transcripts, noting reflections on the salient content of each transcript in the margins; (2) a set of agreed upon themes were collectively generated by the coders; (3) one of the coders (AR) developed a narrative summary of each interview, identifying overall themes. These themes were then presented to the larger study team for discussion and interpretation, and this iterative process was repeated until all transcripts had been read and interpreted; (4) in the final phase of analysis, a set of descriptive and interpretive themes were generated to represent the salient findings across all interviews. Outcomes of the analysis were synthesised and the overarching themes derived from the interviews were developed and critically appraised. Survey data were analysed using the IBM Statistical Package for the Social Sciences 20.0 (SPSS, Armonk, NY, USA), with descriptive statistics used to assess the demographic, clinical, and psychosocial characteristics of the sample.

Results

Demographic and clinical characteristics

The sample comprised 23 participants (15 patients, 8 carers), yielding a response rate of 75%. The mean age of patients was 37 years (SD=14.5; range: 18–59 years), and the mean age of carers was 57 years (SD=16.9; range: 37–75 years). The majority of patients were men (n=9, 60%), whereas five carers were mothers, one a father, and three the wife or long-term partner of a person with VHL. Almost all carers (n=8, 89%), and just over half of patients (n=8, 53%), were married, and all participants had been born in Australia. Ten patients reported some level of tertiary education (67%), whereas half the carers had completed up to Year 10 level at high school (n=4, 50%). Eight patients (53%) had children (M=12.8 years, range: 0–25 years).

Nine patients were diagnosed with VHL due to symptoms (tumours), while six were diagnosed through genetic testing. All patients had undergone genetic testing and had been found to carry a VHL mutation prior to study involvement. The mean age of patients at the time of diagnosis was 26 years (SD=14.2; range: 5–50 years), and the mean time since initial diagnosis was 12 years (SD=10.0; range: 1–34 years). Ten patients reported having one or more tumours at the time of study participation, and 11 patients reported having at least one family member with VHL. The median number of family members diagnosed with VHL was five (range: 1–15 relatives), with three participants being the first person in their family to be diagnosed.

Medical aspects of living with VHL

Screening: a necessary yet anxiety-provoking burden

All patients perceived regular screening as effective in managing VHL and detecting tumours at an early stage. Although some patients described medical screening as a ‘burden’ (n=3), most attended specialist consultations at least yearly and reported never having missed an appointment (n=12). As one carer described: ‘There are benefits to being poked and prodded every year’ (Study ID23, Woman, carer, aged 37 years). The process of waiting for, and receiving, medical test results was an unavoidable reminder of VHL: ‘I’m awaiting MRI results. Waiting on the results has played on my mind’ (ID4, Man with VHL, 44 years). For some, these tests created fear: ‘Last week, the CT scan showed tumours are growing and I need to have further tests – that worries me a lot’ (ID30, Woman with VHL, 53 years). Carers typically accompanied the patient to medical consultations to provide support, to assist in understanding new medical information and to try to alleviate their own worries about the health of their loved one with VHL: ‘When you are told bad news you go blank or numb. The other person is there to listen to what you can’t hear’ (ID38, Woman, carer, 42 years).

Importance of the doctor–patient relationship

Almost all participants described ongoing difficulties in attempting to locate interested, knowledgeable general practitioners to provide personalised medical care: ‘A lot of the doctors we’ve had, they haven’t known about [VHL] and a lot haven’t been interested in finding out’ (ID20, Man, carer, 71 years). Participants’ ongoing relationship with the clinical genetics team was highly valued, not only for the expert medical care provided but also for the bond formed with health professionals who were perceived as interested, knowledgeable, and sensitive to the needs and concerns of the patient and his or her family: ‘We’ve kept in contact with [the clinical geneticist] the whole way through it, and I think that’s a bit of assurance for people in my boat... that there’s someone that you can fall back to, someone you can contact’ (ID4, Man with VHL, 44 years).

Genetic testing, family planning, and perceptions of preimplantation genetic diagnosis

Most patients reported wanting their children to have genetic testing for VHL either at birth (n=3) or before the age of 10 years (n=10). Of the eight patients with children, six had requested genetic testing for their children (mean age of child at the time of genetic test=10.0 years, SD=7.8, range: 0–21 years), and two had unaffected children by utilising preimplantation genetic diagnosis (PGD; ie, genetic screening of embryos before implantation using in vitro fertilisation so that only unaffected embryos are implanted). For four patients, their diagnosis had made them less willing to have children in the future: ‘If I had known [I had VHL] I wouldn’t have had kids’ (ID4, Man with VHL, 44 years). This participant had been severely affected by tumours and one of his young children had already developed symptoms. Most patients (n=10, 71%) perceived PGD as a favourable option to avoid bearing a child with VHL: ‘Our attitude to [having] children never changed, but knowing I had VHL was a major decision in doing PGD to eliminate passing it on to our children’ (ID8, Man with VHL, 31 years). Six patients believed they would not consider pregnancy termination if prenatal testing found the fetus carried a VHL mutation: ‘I would definitely not be interested in having [prenatal testing] to end a VHL-affected pregnancy. But I think this test should be available’ (ID23, Woman, carer, 37 years). The remaining patients were either unsure (n=4) or in support of (n=4) prenatal testing to end an affected pregnancy.

Coping with VHL

Day-to-day coping varies greatly

Some participants experienced difficulties coping with the consequences of VHL, with reminders of the disease ever-present in their lives: ‘[VHL] is always on my mind. It dominates my life, what I can and cannot do. I can’t quite forget it because I mean I’ve got symptoms of imbalance and that sort of thing, so I’m constantly reminded by my symptoms and if I don’t remember them, somebody is bound to remind me’ (ID13, Woman with VHL, 41 years). Participants with more severe symptoms felt that VHL weighed heavily on their life choices and opportunities: ‘[What I feel about VHL is] frustration. It’s a nuisance and there is so much I wish I could still do and I can’t. The symptoms associated with VHL plus hospitalisation and rehabilitation have had a severe impact on my life, career, activities, potential partners, finances and independence’ (ID13, Woman with VHL, 41 years).

In contrast, other participants viewed VHL as having a minor influence on their lives: ‘The way we see it is that it’s a very, very tiny part of our lives, so it’s just a probability issue. There’s a probability that it may happen and there’s a probability that I may get hit by a bus. So it’s not really worthy of a lot of attention’ (ID23, Woman, carer, 37 years). For many, it was important to look to the future and to focus on their family, as well as other aspects of their life: ‘You can’t be negative about it. Life goes on, it’s my children I’ve got to set an example for’ (ID2, Man with VHL, 51 years). Responses to the Brief COPE supported the generally adaptive coping strategies fostered by this group. Strategies of acceptance (M=3.39, SD=0.57), emotional support (M=2.47, SD=1.14), planning (M=2.45, SD=1.13), and positive reframing (M=2.21, SD=1.11) were the most highly endorsed coping methods, whereas denial (M=1.11, SD=0.36), behavioural disengagement (M=1.21, SD=0.48), and self-blame (M=1.32, SD=0.65) were the least endorsed.

Role of family in living with VHL

‘I got you babe’: the importance of partner support

Partner support was described as important and beneficial for most participants: ‘When I was diagnosed [my wife and I] had only been together six months and she’s just been fabulous from the word go’ (ID8, Man with VHL, 31 years). Many participants believed their marriages had grown stronger as a result of VHL, and described a sense of emotional security in their relationship: ‘It’s actually been good for [our marriage] I think. It’s brought us closer together. I’ve got that security. I know that if she’s stuck with me through this, she’s not just going to walk out on me’ (ID7, Man with VHL, 58 years).

Family matters: the impact of VHL on family roles and relationships

Family support was also perceived as important, particularly for younger patients: ‘Mum is the reason I’m probably still here, because mum keeps track of everything and says, ‘Okay, don’t forget in a month’s time we’ve got this appointment’. She’ll keep me up-to-date’ (ID31, Man with VHL, 23 years). On a practical level, screening was often a family affair: ‘We book [screening appointments] all on the same day, so it is like a family trip in, so it just makes it a lot easier’ (ID28, Man with VHL, 21 years). Having VHL in common with other family members strengthened relationships for some: ‘Obviously my mum goes through the same thing that I do so we talk quite often about it and from that point-of-view, I guess it’s brought us a lot closer together and we share experiences, you know, every time we have our tests’ (ID8, Man with VHL, 31 years).

Most participants felt it was easier to talk about VHL with family members who carried a VHL mutation, compared with those who did not. Some participants discussed the desire for greater empathy and involvement from unaffected relatives, particularly siblings: ‘Well I avoid talking about [VHL] with my siblings, because I know they don’t understand or don’t want to’ (ID13, Woman with VHL, 41 years). Others reported times when they felt isolated within the family and fearful of the possible future consequences of VHL: ‘It’s traumatic for me to hear about VHL in any format but to have a family without the disorder and having to outline all of the outcomes makes it even worse’ (ID4, Man with VHL, 44 years). This sense of isolation was most prominent in the narratives of participants who were the first in their family to be diagnosed: ‘I think because you’re the only one, you haven’t got anyone that had got it to talk to’ (ID13, Woman with VHL, 41 years).

Some participants described feelings of transmission guilt (an intense sense of guilt about having passed VHL onto one's children): ‘It actually made my mother quite distraught... it actually upset her quite a bit. She felt pretty bad that she’d given this to me’ (ID8, Man with VHL, 31 years). For one father, feelings of guilt, anger, and sadness had become obstacles in his relationships with his children: ‘The children with it [VHL], I’ve become a little bit more detached from. I’m guilty, I’m the culprit. [My children] told me straight to my face, ‘you’re the one who’s given it to me’ (ID4, Man with VHL, 44 years).

Negotiating the disparate needs of their children with and without VHL was also difficult territory for carers, with some carers daunted by the challenge of trying to ‘be fair’ in their treatment of unaffected children while also taking into consideration the lack of opportunities that may be availed to their child with VHL: ‘We’re both getting on in years and we have to think, well if [our daughter] does survive us we’ve got to provide for her, and it makes it difficult with all the other children if we plan to give her the means of survival and they miss out. It’s a very difficult thing to work out actually, to make it fair and to make the others understand that it’s not because we don’t want to help them, it’s because we feel that she’s got to be helped because she’s helpless in a way’ (ID19, Woman, carer, 75 years).

Thinking about the future with VHL

Perceived financial and career limitations

Some participants perceived their livelihood as heavily influenced by the medical challenges associated with VHL. Career choices and opportunities were often viewed differently once symptoms started to manifest: ‘I’ve always just done basic small work, not trying to go up the ladder, not trying to get more money. I was working for myself with a builder’s licence and I thought things were pretty good and next thing I know I’m in hospital having brain tumours and it sort of knocks you around’ (ID7, Man with VHL, 58 years). Several patients and carers shared their concerns about employment and financial security: ‘When I first started with the disease, I had to take so much time off my old job that eventually I was made redundant and I lost my job. So I was apprehensive first off coming to this [new] company just thinking, ‘Well, if I have to do that again, I would probably get fired again’ (ID31, Man with VHL, 23 years).

Although most patients had not encountered workplace discrimination relating to their condition (n=14), many remained hesitant to disclose their diagnosis to employers and colleagues. The need to communicate to employers about VHL was also perceived as a significant barrier to career progression: ‘I started looking for another job and I actually got a couple of offers, but I was a nervous wreck wondering, ‘What the hell do I tell these people about VHL?’, you know’ (ID7, Man with VHL, 58 years). Two carers expressed feelings of helplessness and frustration in regards to the way their daughter was treated at work: ‘People seem to think that because she’s had several brain tumours, she’s not the full quid – which is wrong. She’s often made fun of at work, for instance. It’s not very kind. I get really cross. I can’t do anything about it’ (ID19, Woman, carer, 75 years).

Psychological consequences of VHL

Psychological well-being

Of the 19 participants (14 patients, 5 carers) who completed the IES, one carer reported symptoms indicative of significant traumatic stress warranting clinical assessment. Of the 13 patients who completed the HADS, six patients (46%) reported anxiety, and two patients reported (15%) depressive symptoms, warranting clinical assessment. The anxiety symptom, ‘I feel restless, as if I have to be on the move’ was most strongly endorsed, with seven patients (54%) experiencing this symptom ‘quite a lot’ or ‘very much indeed’ in the past week. Of the five carers who completed the HADS, one carer reported anxiety, and another carer reported depressive symptoms, indicative of the need for clinical assessment.

A sense of isolation and detachment from peers

For some, physical impairments associated with VHL had resulted in the loss of particular social, occupational, or sporting activities, which in turn often resulted in the loss of friendships and a narrowing of one’s social network: ‘[VHL] basically drained me all the time and I wasn’t going out and I was always tired. I never went out, hardly did anything with friends, lost a lot of friends because of it’ (ID31, Man with VHL, 23 years).

Caring with little or no reprieve

Most carers reported little respite from the instrumental and emotional support they provided. One carer had sought professional psychological support to help her during a particularly difficult period. Two carers identified gaps in emotional support for themselves: ‘It’s very stressful because it impacts on your whole life. It’s not just when they’re sick and have got an operation coming up… it’s the aftermath and the things that happen afterwards that are caused by the operation itself. They don’t seem to recover completely. We stay at home a lot’ (ID19, Woman, carer, 75 years). Consistent with this, two of the five carers who completed the Carer Burden Scale reported experiencing a significant burden because of their current care-giving responsibilities.

Information and support needs

Patients and carers identified booklets (n=18), genetic counsellors (n=18), and medical doctors (n=11) as their most commonly accessed sources of information about VHL. Most participants reported feeling satisfied with general information about VHL, as well as information regarding medical decision-making (see Table 2). Pregnancy was one issue about which participants felt there was insufficient information and support: ‘Whilst I was pregnant I found it hard because there’s no information available for pregnant people with VHL – that’s the hardest part. I felt like I didn’t have enough information. I didn’t know where to turn’ (ID10, Woman with VHL, 34 years). Almost all participants reported some level of dissatisfaction with the quality and quantity of information about legal and financial support for affected families, as well as advice on how to communicate with others about VHL. The Internet, medical consultations, and a decision aid were rated as the most potentially useful sources of information (see Figure 1). Support groups received mixed responses, with some participants perceiving support group interactions as difficult, particularly when meeting others who were more adversely affected than themselves. Others perceived the need for an Australian support group where they could connect with other people with VHL: ‘It’s probably why we hang on to [the VHLFA booklet] so much, you know, because it’s like, ‘Hey, there’s others out there!’ (ID4, Man with VHL, 44 years).

Discussion

Despite well-established protocols for the medical management of VHL, families in this study reported a range of emotional, social, and practical challenges, including: sustained uncertainty about future tumour development, frustration regarding the need for lifelong screening, strained family relationships, perceived isolation from peers and colleagues, limited career opportunities, concerns about financial security, complex decisions in relation to childbearing, and difficulties gaining access to appropriate and timely support. Carers, too, reported considerable challenges, such as little reprieve from care-giving responsibilities, difficulties balancing the needs of VHL-affected and unaffected family members, fears about the future, and, for some, guilt regarding the onset of tumours in their children. Further, while some participants acknowledged the availability of an informal peer support group affiliated with the VHL Family Alliance, many had initially struggled to find reliable information on personally relevant topics and to connect with others affected by the disease. Overall, these results do bear some semblance to those reported by our Dutch colleagues;10 however, a greater proportion of patients in this Australian sample expressed positive attitudes towards PGD (71% in present sample versus 33% in the Dutch sample19). Although the exact reason for this variation in results is unclear, it is possible that cultural, methodological, attitudinal, and clinical factors may each have some role, and future studies exploring the potential contributions of these factors would be valuable.

Although screening for tumours was universally perceived as important and effective, participants nevertheless experienced a range of emotional and practical difficulties in association with medical interactions, including anxiety before medical consultations and while awaiting test results. For those in employment, time away from work to attend medical appointments was perceived as an ongoing source of stress, as some had previously lost their jobs because of absenteeism. In addition, there was often a perceived lack of continuity in care, with medical care (particularly general medical care) viewed by some participants as fragmented and uncoordinated. Consequently, several participants reported infrequent consultations with a general physician. For some, it was only once they had met with the clinical genetics team that they perceived their health care to be holistic, empathic, and person-centred, highlighting the important role genetic counsellors have in identifying the needs of patients and families, and coordinating pathways to care.

The consequences of VHL in terms of family functioning and relationships varied widely. This is not unexpected, given the diversity of family dynamics and the varied ways in which families can respond to illness (eg, Buchbinder et al,20 Koehly et al,21 Peters et al,22 and Ozone et al23). Although some participants reported a strengthening of familial bonds brought about by VHL-related experiences, others reported significant ruptures in their family relationships, including sibling rivalry, communication difficulties, and strong feelings of guilt. Family-based psychological support focused on better understanding the unique as well as shared views, experiences, challenges, and coping responses of each person within the family may be particularly valuable when working with families affected by VHL.

Several carers in this study reported ongoing uncertainty, anxiety, and frustration in relation to their family member’s health, as well as the limitations imposed on their lifestyle as a consequence of their care-giver role. Overall, it is estimated that informal carers attend to over 50% of cancer patients’ care needs throughout their illness,24 and studies show that carers face a greater prevalence of psychological difficulties compared with healthy peers,10, 25 with 18–58% of caregivers estimated to experience clinical depression.26 Other studies have suggested that long-term care-giving is associated with poorer health outcomes.27 More research aimed at understanding the factors predictive of difficulties associated with care-giving is needed. Incorporating brief screening tools for psychological distress and supportive care needs into routine care for both patients and carers may assist health care professionals in better addressing these issues, and is warranted given the desire for greater support documented in this and previous studies.10, 11

Patients and carers also openly discussed challenges with regard to finances and career opportunities. Many participants were hesitant to disclose their diagnosis for fear of workplace stigma and felt they lacked the confidence or support to talk with employers or colleagues about VHL. Greater support was also desired regarding financial and legal entitlements. Reports from other cohorts have emphasised the physician’s potential role in facilitating a person’s return to work after cancer,28 and this seems critical for a condition where recurrent tumours are likely to create multiple interruptions to one’s working life. Research evaluating the potential value of Question Prompt Sheets29 (or similar tools) to facilitate greater communication between clinicians, patients, and carers on these issues is needed.

Study strengths and limitations

This study provides rich, in-depth information about the lived experiences of Australian families affected by VHL, and the results indicate a clear need for greater continuity of medical and psychosocial care for patients and their carers. However, the present study was not without limitations. The cross-sectional study design precludes causal inferences about the patterns observed, while the small sample size limits the generalisability of results (especially for carers), and prevents comparisons of psychological distress scores with previous studies, as well as comparisons between patients with different clinical features. Despite these limitations, the results suggest that more sophisticated systems for connecting patients and families with holistic, empathic, and person-centred medical and psychosocial care are urgently needed. Web-based applications, including interactive educational resources, easy-to-understand scientific updates, chat forums, and professional webinars, may be one means of economically delivering information and support. In addition, different clinical presentations of VHL may be associated with differing psychological responses; for example, transmission guilt may be higher in families where parents see their children seriously affected at younger ages, and unresolved grief may be more common among families that have suffered multiple deaths due to VHL. These possibilities merit further investigation in larger samples.

References

Maher E, Iselius L, Yates J et al: Von Hippel–Lindau disease: a genetic study. J Med Genet 1991; 28: 443–447.

Shuin T, Yamasaki I, Tamura K, Okuda H, Furihata M, Ashida S : Von Hippel–Lindau disease: molecular pathological basis, clinical criteria, genetic testing, clinical features of tumors and treatment. Jpn J Clin Oncol 2006; 36: 337–343.

Maher ER, Yates JR, Harries R et al: Clinical features and natural history of von Hippel–Lindau disease. Q J Med 1990; 77: 1151–1163.

Lonser RR, Glenn GM, Walther M et al: von Hippel-Lindau disease. Lancet 2003; 361: 2059–2067.

Wilding A, Ingham SM, Lalloo F et al: Life expectancy in hereditary cancer predisposing diseases: an observational study. J Med Genet 2012; 49: 264–269.

Couch V, Lindor N, Karnes P, Michels V : von Hippel–Lindau Disease. Mayo Clinic Proc 2000; 75: 265–272.

Wertz D, Fanos J, Reilly P : Genetic testing for children and adolescents: Who decides? JAMA 1994; 272: 875–881.

Giarelli E : Self-surveillance for genetic predisposition to cancer: Behaviors and emotions. Oncol Nurs Forum 2006; 33: 221–231.

Rasmussen A, Alonso E, Ochoa A et al: Uptake of genetic testing and long-term tumor surveillance in von Hippel–Lindau disease. BMC Med Genet 2010; 11: 1–9.

Lammens C, Bleiker E, Verhoef S et al: Psychosocial impact of Von Hippel–Lindau disease: levels and sources of distress. Clin Genet 2010; 77: 483–491.

Lammens C, Bleiker E, Verhoef S et al: Distress in partners of individuals diagnosed with or at high risk of developing tumors due to rare hereditary cancer syndromes. Psycho-Oncol 2011; 20: 631–638.

Miles MB, Huberman AM : Qualitative Data Analysis: An Expanded Sourcebook 2nd edn. London, UK: Sage Oublications, 1994.

Patton M : Qualitative Evaluation and Research Method 2nd edn. London, UK: Sage Publications, 1990.

Horowitz M, Wilner N, Alvarez W : The Impact of Event Scale: a measure of subjective stress. Psychosom Med 1979; 41: 209–218.

Cella D, Mahon SM, Donovan M : Cancer recurrence as a traumatic event. Behav Med 1990; 16: 15–22.

Zigmond A, Snaith R : The Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1983; 67: 361–370.

Carver CS : You want to measure coping but your protocol’s too long: Consider the Brief COPE. Int J Beh Med 1997; 4: 92–100.

Bedard M, Molloy D, Squire L, Dubois S, Lever J, O’Donnell M : The Zarit Burden Interview: a new short version and screening version. Gerontologist 2001; 41: 652–657.

Lammens C, Bleiker E, Aaronson N et al: Attitude towards pre-implantation genetic diagnosis for hereditary cancer. Fam Cancer 2009; 8: 457–464.

Buchbinder D, Casillas J, Krull K et al: Psychological outcomes of siblings of cancer survivors: a report from the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. Psycho-Oncol 2011; 20: 1259–1268.

Koehly LM, Peters JP, Kenen R et al: Characteristics of health information gatherers, disseminators, and blockers within families at risk of hereditary cancer: implications for family health communication interventions. Am J Public Health 2009; 99: 2203–2209.

Peters J, Kenen R, Hoskins L et al: Unpacking the blockers: understanding perceptions and social constraints of health communication in hereditary breast ovarian cancer (HBOC) susceptibility families. J Genet Couns 2011; 20: 450–464.

Ozono S, Saeki T, Mantani T et al: Psychological distress related to patterns of family functioning among Japanese childhood cancer survivors and their parents. Psycho-Oncol 2010; 19: 545–552.

Nijboer C, Tempelaar R, Sanderman R : Cancer and caregiving: the impact on the caregiver's health. Psychooncology 1998; 7: 3–13.

Northouse L, Stetz K : A longitudinal study of the adjustment of patients and husbands to breast cancer. Oncol Nurs Forum 1989; 16: 511–516.

Kurtz M, Kurtz J, Given C, Given B : Relationship of caregiver reactions and depression to cancer patients’ symptoms, functional states and depression: a longitudinal view. Soc Sci Med 1995; 40: 837–846.

Aubeeluck A : Caring for the carers: quality of life in Huntington’s disease. Br J Nurs 2005; 14: 452–454.

Bauman LJ, Drotar D, Leventhal JM, Perrin EC, Pless IB : A review of psychosocial interventions for children with chronic health conditions. Pediatrics 1997; 100 (2 Pt 1): 244–251.

Dimoska A, Tattersall MH, Butow PN, Shepherd H, Kinnersley P : Can a “prompt list” empower cancer patients to ask relevant questions? Cancer 2008; 113: 225–237.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the valuable contributions of all of the people who participated in this research. Dr Kasparian is supported by a Career Development Fellowship from the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia (NHMRC ID 1049238). Ms Sansom-Daly is supported by a Leukaemia Foundation of Australia PhD Scholarship. This project was also supported by an Early Career Researcher Award from UNSW Medicine, University of New South Wales (N Kasparian).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Kasparian, N., Rutstein, A., Sansom-Daly, U. et al. Through the looking glass: an exploratory study of the lived experiences and unmet needs of families affected by Von Hippel–Lindau disease. Eur J Hum Genet 23, 34–40 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1038/ejhg.2014.44

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/ejhg.2014.44

This article is cited by

-

Disclosure of genetic risk to dating partners among young adults with von Hippel-Lindau disease

Familial Cancer (2023)

-

Carer burden in rare inherited diseases: a literature review and conceptual model

Orphanet Journal of Rare Diseases (2022)

-

Minors at risk of von Hippel-Lindau disease: 10 years’ experience of predictive genetic testing and follow-up adherence

European Journal of Human Genetics (2022)

-

“Getting ready for the adult world”: how adults with spinal muscular atrophy perceive and experience healthcare, transition and well-being

Orphanet Journal of Rare Diseases (2019)

-

Genetic Counseling in Von Hippel-Lindau Disease: Navigating the Landscape of a Well-Established Syndrome

Current Genetic Medicine Reports (2017)