Exclusive breast-feeding for the first 6 months of life is a powerful health-promoting behaviour not consistently adopted(Reference Jones, Steketee and Black1, Reference Bryce, el Arifeen and Pariyo2). Moreover, there is growing evidence that exclusive and prolonged breast-feeding improves maternal/infant health in both developing and developed countries(Reference Horta, Bahl and Martinés3–Reference Leon-Cava, Lutter and Ross6) and promoting it may be cost-effective(Reference Bartick and Reinhold7). The WHO/UNICEF Baby-Friendly Hospital Initiative (BFHI) is an effective strategy to increase breast-feeding exclusivity and duration(Reference Kramer, Chalmers and Hodnett5) but many countries have been slow to implement it(8).

In fact, compliance with the Initiative's policies and practices, outlined in the Ten Steps to Successful Breastfeeding (Ten Steps, see Table 1) and the International Code of Marketing of Breastmilk Substitutes (Code)(8, 9), requires formulating adequate policy as well as a detailed revision of pre-, peri- and postnatal services to support a change in paradigm where the mother/baby dyad is the centre of the process of care. Once Baby-Friendly status is achieved, recertification – or monitoring compliance – after initial designation poses another challenge. For example, although breast-feeding duration may decrease with deteriorating compliance in designated facilities(Reference Merten, Dratva and Ackermann-Liebrich10), only Switzerland reports to systematically monitor Baby-Friendly practices once a hospital has been certified for the initial period(11); other countries rely, if anything, only on recertification procedures(Reference Moura de Araujo Mde and Soares Schmitz Bde12). Since the introduction of more rigorous BFHI revised standards in 2006, countries are also faced with challenges in implementing them, particularly in regard to skin-to-skin contact (immediately after birth for at least an hour, unless medically justified), rooming-in (no mother/baby separation allowed, unless justified) and in applying these standards to caesarean deliveries(8).

Table 1 The Ten Steps to successful breast-feeding

Source: WHO/UNICEF (2009) Baby-Friendly Hospital Initiative. Revised, Updated and Expanded for Integrated Care. Section 1: Background and Implementation (8).

Monitoring BFHI compliance

Several publications have reported diverse methods to measure compliance with standards promoted by the BFHI(Reference Merten, Dratva and Ackermann-Liebrich10, 11, Reference Campbell, Gorman and Wigglesworth13–30). For example, whereas most rely on surveys, Swiss authors report continuously monitoring targeted BFHI hospital practices(Reference Merten, Dratva and Ackermann-Liebrich10, 11). Also, most of these studies are designed to measure associations between BFHI exposure and breast-feeding behaviours and to measure BFHI compliance they generally resort to only one of the information sources proposed for the official designation(8): hospital staff and/or managers(Reference Cattaneo and Buzzetti14, 15, Reference Dodgson, Allard-Hale and Bramscher19, Reference Kovach21–Reference Levitt, Kaczorowski and Hanvey23, Reference Rosenberg, Stull and Adler26, Reference Syler, Sarvela and Welshimer27, Reference Grizzard, Bartick and Nikolov29) or pregnant women/mothers(Reference Declercq, Labbok and Sakala16–Reference DiGirolamo, Grummer-Strawn and Fein18, Reference Murray25, Reference Chalmers, Levitt and Heaman28) cared for in the facility; only two studies used both sources(Reference Martens, Phillips and Cheang24, 30) and two older studies also included observations of maternity units(Reference Campbell, Gorman and Wigglesworth13, Reference Gokcay, Uzel and Kayaturk20). No recent publication has triangulated these three data sources to analyse biases contributed by each source. Likewise, with the exception of reports on Nicaraguan(31), Swiss(11) and CDC monitoring initiatives(15, Reference Murray25, 32), little has been published about effective strategies or tools to convey to authorities and health-care professionals results about BFHI compliance that may help them improve practice(Reference Jamtvedt, Young and Kristoffersen33).

Furthermore, no computerized assessment method or tool is available to measure – and disseminate – compliance with the updated BFHI, using three information sources. WHO/UNICEF have developed a computerized tool to use in external hospital assessments for BFHI designation, therefore with restricted access(8). It is intended to collect information in compliance with standards and does not require systematic recording of (i) information on non-compliant answers/observations or (ii) qualitative data provided by participants or noted in observations. Also, the completed tool is not returned to evaluated hospitals. For monitoring purposes, WHO/UNICEF suggest different strategies including use of a paper tool(34) but there have been no publications reporting its use or accuracy. Although an evaluation method developed in Brazil has been tested and published(Reference de Oliveira, Camacho and Tedstone35), no computerized tools are available to assess/monitor compliance with a BFHI expansion to community health centres (CHC).

The present paper describes the development of a comprehensive, bilingual, computer-based tool to collect, summarize and disseminate information on policies and practices outlined in the BFHI intended for policy makers, public health authorities, hospital managers, physicians, nurses and other health-care professionals caring for families. The tool supports both normative and formative assessments because it not only measures compliance with evidence-based international standards but it can also contribute to the planning process by giving facilities detailed feedback on which improvements are needed(34).

Tool development

In response to successive provincial policy statements prioritizing the BFHI, the public health authority of the Montérégie (second largest socio-sanitary region in the province of Québec, Canada) developed an assessment tool in 2001 to monitor hospital compliance with BFHI indicators. In 2007, the tool was revised and renamed BFHI-40 Assessment Tool(Reference Haiek and Gauthier36). This version of the tool was used in a large study assessing BFHI compliance in sixty birthing facilities across the province of Québec, including nine hospitals in the Montérégie(Reference Haiek37). Hence, the Montérégie has benefited from a baseline assessment in 2001 for its nine hospitals(Reference Haiek, Brosseau and Gauthier38) (performing over 12 000 deliveries annually) and follow-up assessments in 2004 and 2007(Reference Haiek37). Assessments were approved by the Ethics Committee of Charles LeMoyne Hospital (a university-affiliated hospital with regional mandates).

While describing the development of the tool(Reference Haiek and Gauthier36), results from the 2007 assessment for one of the nine hospitals (Hospital F, 1700 annual deliveries) and for the region (mean of all Montérégie hospitals) are presented to illustrate the type of information returned to individual hospitals and regional authorities. Participants from the nine hospitals included nine to fifteen staff/managers (ten for Hospital F, total of ninety-four) and nine to forty-five breast-feeding mothers (thirty-five for Hospital F, total of 176). Participating staff were randomly selected among those present during the interviewer-observer's 12 h hospital visit (91 % response rate for Hospital F and 92 % for the Montérégie). Mothers were selected randomly from birth certificates and answered telephone interviews (88 % response rate for both Hospital F and the Montérégie) when their babies were on average 2 months old (73 d for Hospital F and 72 d for the Montérégie).Footnote * Six per cent of Hospital F and 15 % of Montérégie mothers delivered by caesarean section under epidural.Footnote † Lastly, observations targeted documentation and educational/promotional materials; in this particular assessment, observations of postpartum mother/baby dyads were optional.

The following steps were followed to develop the tool.

1. Defining indicators for the Ten Steps and the Code

Using the BFHI as a framework, one to seven ‘common’ indicators (see explanation below) were formulated to measure each step and the Code, totalling forty (referred to in the tool's name). Most of these indicators were originally defined respecting the 1992 BFHI's Global Criteria(39) and were revised to comply with 2006 criteria(8). ‘Common’ indicators are measured using one, two or three perspectives or sources of information: (i) maternity unit staff (including physicians) and managers (usually head nurses); (ii) pregnant women and mothers; and (iii) external observers. For example, as shown in Table 2, Step 4 has four ‘common’ indicators, each measured using staff/managers and mothers, resulting in eight indicators for the step (four for staff/managers and four for mothers).Footnote *

Table 2 Four ‘common’ indicators and corresponding eight indicators for Step 4 of the Baby-Friendly Hospital Initiative

Each indicator is measured with one or two questions (mostly open-ended) or observations. Questions were originally(Reference Haiek, Brosseau and Gauthier38) developed integrating the 1992 criteria(39), previously tested questionnaires(Reference Martens, Phillips and Cheang24, Reference Lepage and Moisan40, Reference Kovach41) and multidisciplinary experts’ opinion. They were revised twice(Reference Haiek and Gauthier36, Reference Haiek, Gauthier and Brosseau42) to update recommendations(8) and improve content validity.

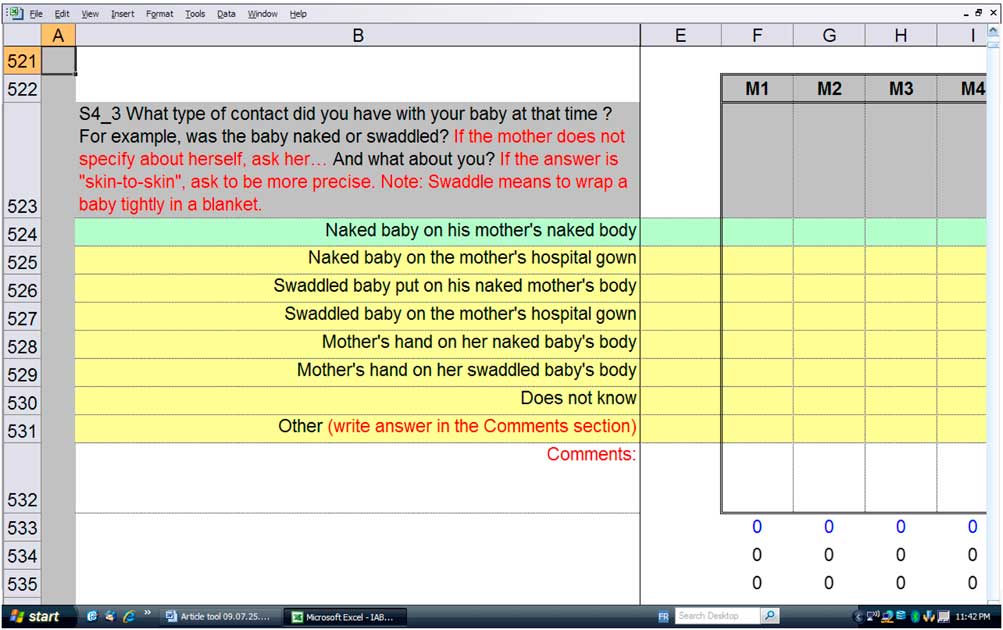

To enhance comparability, formulation of questions measuring a given policy or practice (and the corresponding indicator) is similar or identical for each perspective. Each question and observation is followed by colour-coded compliant (green) and non-compliant (yellow) categories (Fig. 1) where the interviewer summarizes answers and observations; a line intended for comments allows the interviewer/observer to record answers not listed as well as qualitative information offered by respondents.

Fig. 1 Example of a question used to measure a Step 4 indicator (mothers’ perspective)

The tool comprises questions to measure indicators not specifically addressed by the Global Criteria but that yield useful information. For example, despite being subject since 2006 to equal standards, questions for Step 4 are asked separately for vaginal and caesarean deliveries. The tool also includes information on potential institutional- and individual-level variables.

2. Measuring indicators’ extent of implementation

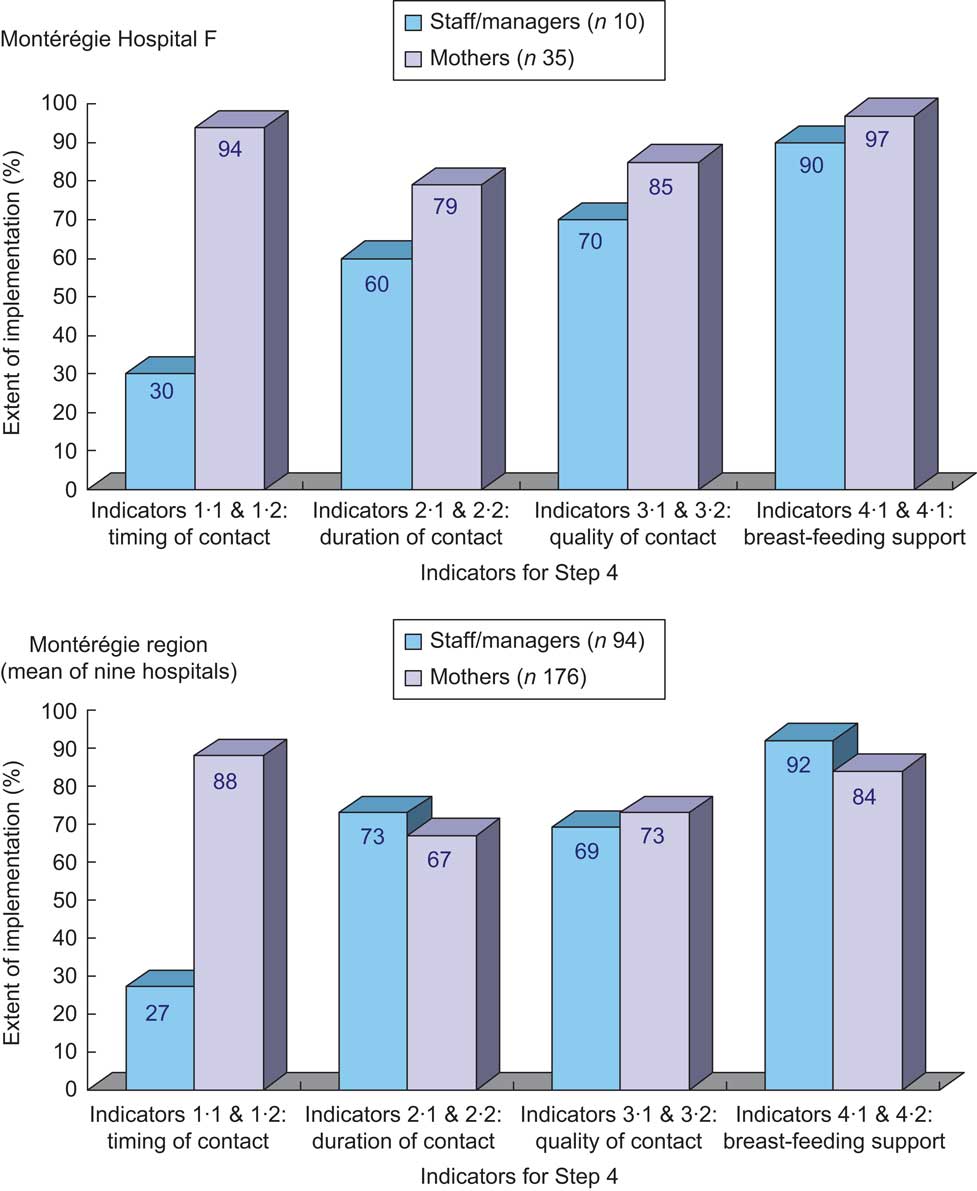

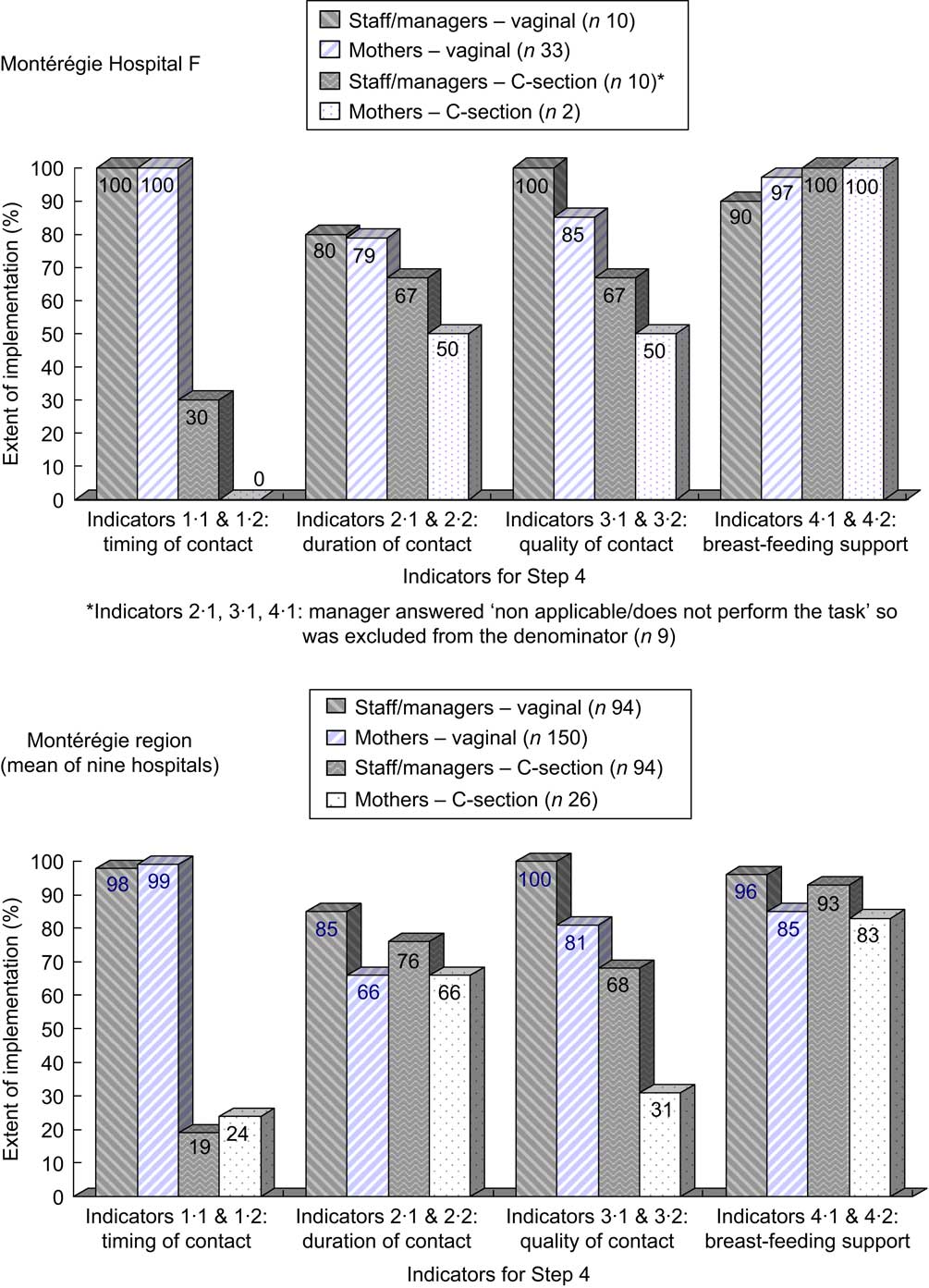

The extent of implementation of a given indicator is obtained by calculating the percentage of compliant or ‘correct’ answers/observations. Figure 2 illustrates results for Step 4 indicators for the ‘example’ Montérégie hospital (Hospital F) and the regional mean.

Fig. 2 Compliance with Step 4 as measured by the extent of implementation of the step's indicators in Montérégie Hospital F and the Montérégie region, 2007

For example, three out of ten staff/managers in Hospital F report placing mother and baby in contact immediately after a delivery – vaginal or caesarean under epidural – or within the first 5 min (extent of implementation of 30 %), whereas thirty-three of thirty-five mothers delivering vaginally or by caesarean in this hospital report having benefited, unless medically justifiably, from this early contact with their babies (extent of implementation of 94 %). Precision of calculated percentages varies according to the extent of implementation of the indicator and sample sizes. Using the same example, the proportion (%) and 95 % CI of the indicator measuring timing of contact is 30 % (2 %, 58 %) for staff/managers and 94 % (86 %, 100 %) for mothers. The extent of implementation of the other indicators can be interpreted in the same manner.

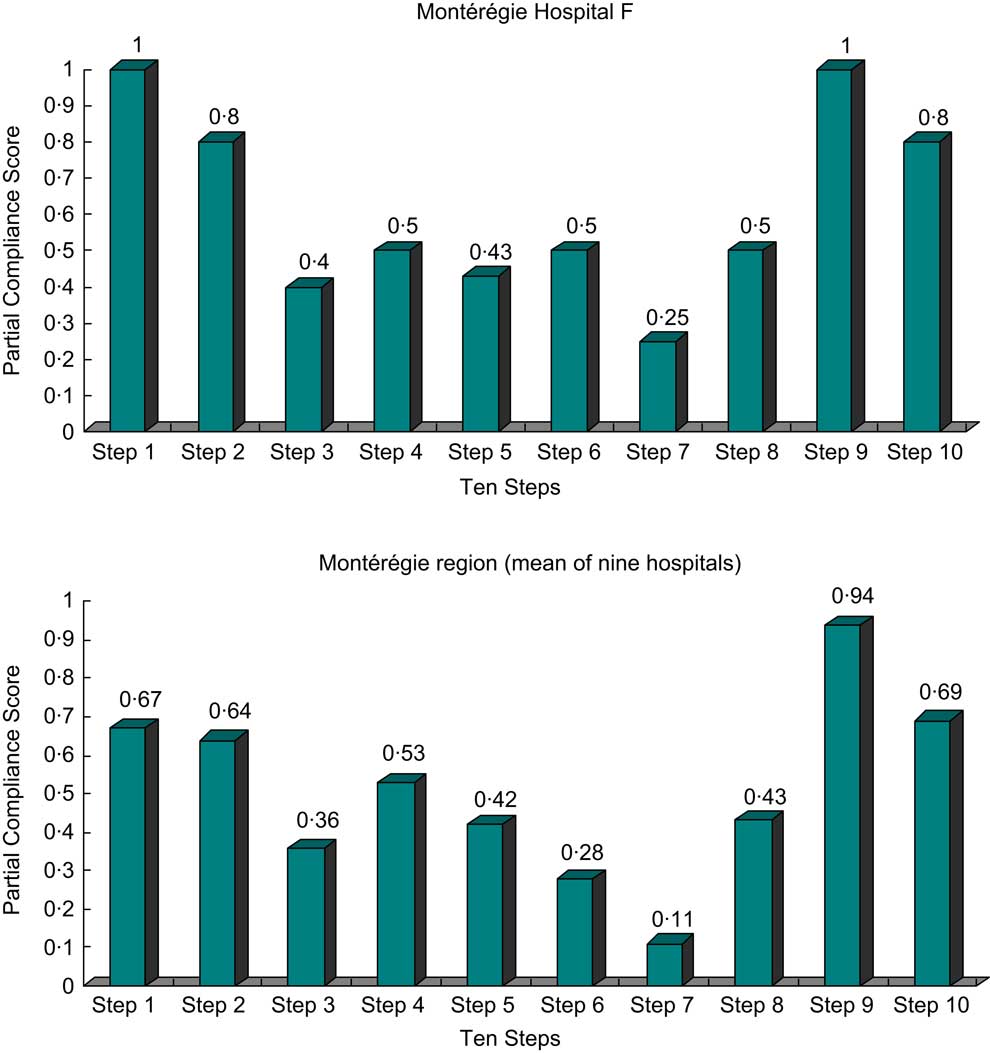

Results analysed by type of delivery show staff/managers and mothers are more likely to report early and prolonged ‘true’ skin-to-skin contact for vaginal deliveries than for caesarean section (C-section; Fig. 3). They also show a consistently low dissimilarity indexFootnote * (i.e. 15 % or under) between staff/managers and mothers for all indicators related to vaginal deliveries. Conversely, the dissimilarity between sources is high (i.e. greater than 15 %) for the indicators measuring quality of skin-to-skin contact for caesarean deliveries.

Fig. 3 Compliance with Step 4 as measured by the extent of implementation of the step's indicators in Montérégie Hospital F and the Montérégie region, by type of delivery, 2007

This example illustrates how collecting separate data may help to interpret, in this case, the up-dated skin-to-skin standards. Thus, higher compliance with Indicator 1 reported by mothers in the combined analysis (Fig. 2) can be explained by the fact 85 % of them delivered vaginally and report their favourable experience with this type of delivery (the majority of vaginal birth experiences in the sample drives overall compliance up), whereas the staff had to report compliant practices for both vaginal and caesarean deliveries (their report on caesareans drives overall compliance down).

3. Establishing compliance

To consider an indicator completely implemented, its extent of implementation has to attain a pre-established threshold. The tool is prepared to assess compliance with an 80 % threshold (for example, at least 80 % of mothers report they were put in skin-to-skin contact with their baby according to a compliant definition).Footnote * To summarize compliance, composite scores were constructed for each step (partial scores) and for all Ten Steps and the Code (global scores).

Step Partial Compliance Score

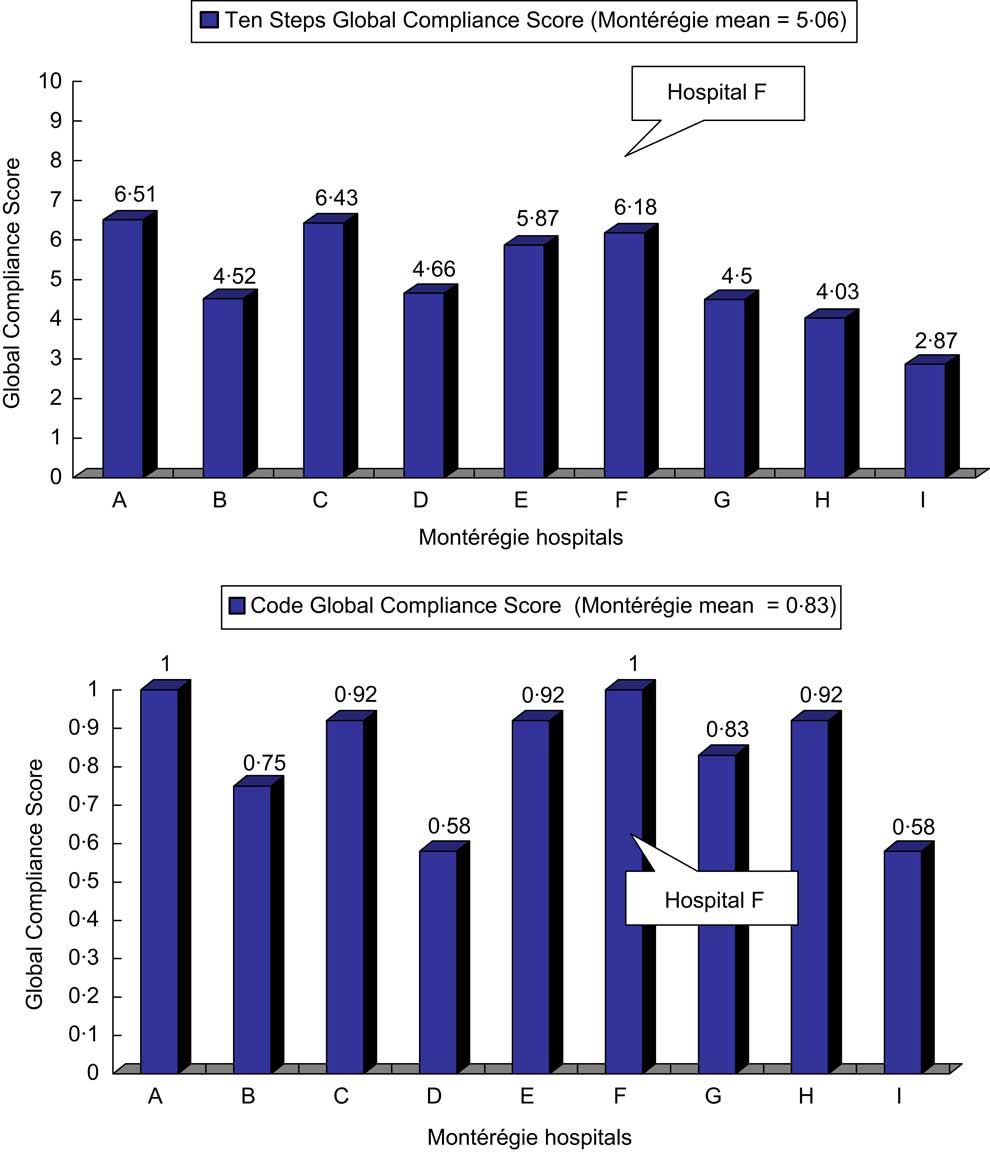

To build the Partial Compliance Score for each of the Ten Steps, a value of 0 or 1 point is attributed to each indicator based on its extent of implementation. Hence, a value of 0 denotes that the indicator is not completely implemented (i.e. its extent of implementation does not reach the threshold) and a value of 1 denotes that the indicator is completely implemented (i.e. its extent of implementation reaches the threshold). The score is then calculated by adding all the points attributed to each indicator of the particular step divided by the maximum amount of points that would be accumulated if all the step's indicators were completely implemented, resulting in a score that varies between 0 and 1. For example, a Step 4 Partial Compliance Score of 0 indicates that none of the eight indicators measuring step compliance are completely implemented; a score of 0·25, that two of the eight indicators are completely implemented; and a score of 1, that all eight indicators are completely implemented. Figure 4 shows Partial Compliance Scores calculated with an 80 % threshold for each step for Hospital F and the Montérégie.

Fig. 4 Partial Compliance Scores for each of the Ten Steps for Hospital F and the Montérégie region, 2007

Ten Steps and Code Global Compliance Scores

The Ten Steps Global Compliance Score is obtained by adding the individual steps’ Partial Compliance Scores and, therefore, varies between 0 and 10. The Code Global Compliance Score is calculated the same as a Step Partial Compliance Score, ranging also between 0 and 1.

Figure 5 shows 2007 global scores for the Montérégie hospitals. The Ten Steps Global Compliance Score varied among hospitals between 2·87 and 6·51 (regional mean of 5·06) whereas the Code Global Compliance Score varied between 0·58 and 1 (regional mean of 0·83). Because of the way the score is constructed, its validity in measuring a hospital's true BFHI compliance depends on the precision of each indicator's extent of implementation. As explained above, their precision varies with sample size and the variability for which the measured policy or practice is implemented or reported.

Fig. 5 Global Compliance Scores for the Ten Steps and the Code, Montérégie region hospitals, 2007

4. Monitoring compliance

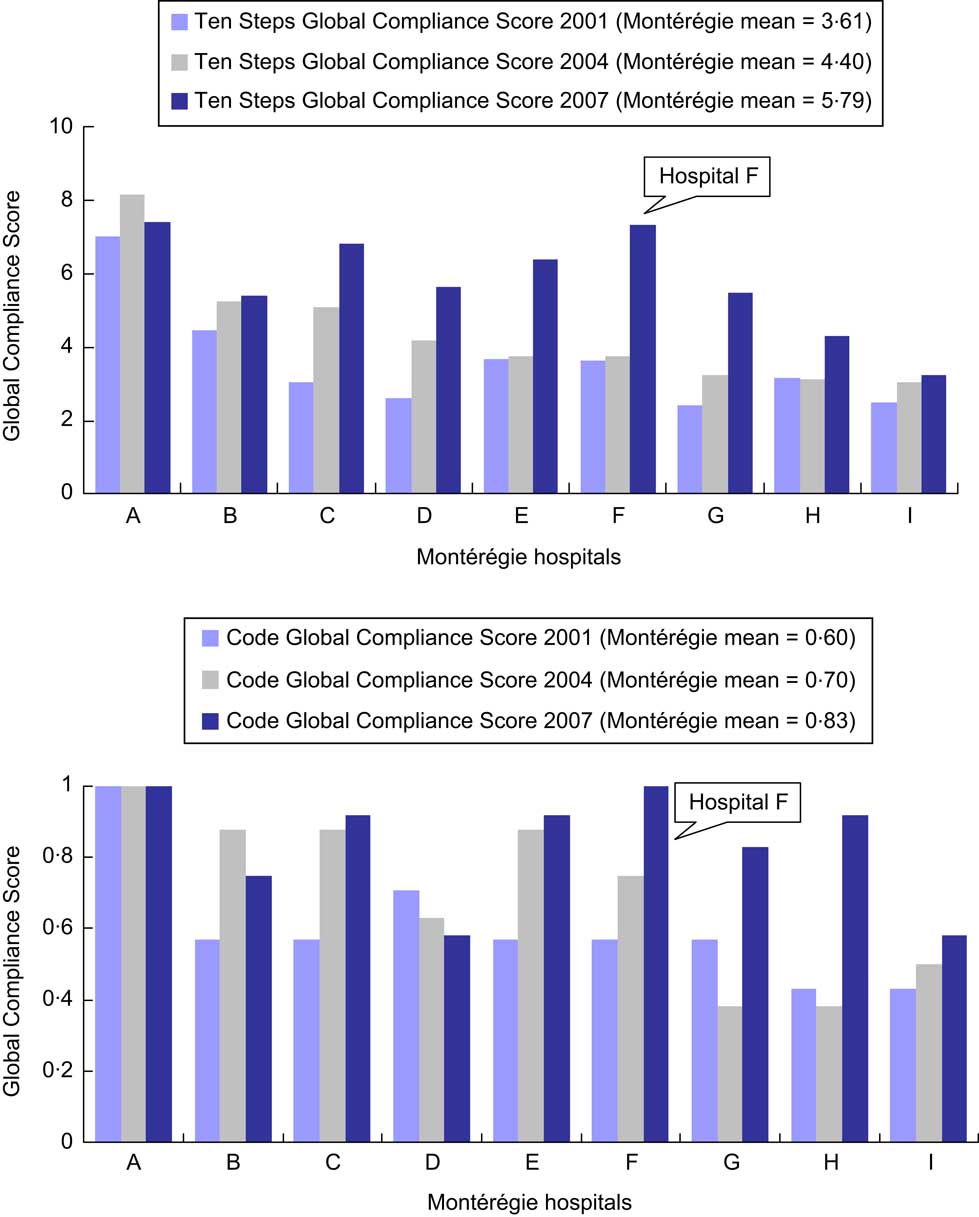

Figure 6 shows the evolution of the Global Compliance Score for the Montérégie hospitals. To assure comparability between assessments, 2007 scores were recalculated using the same methodology as in 2001 and 2004 (based on 1992 Global Criteria and a slightly different attribution of points). This results in an increase of the Ten Steps Global Compliance Score from 6·18 to 7·33 for Hospital F and from 5·06 to 5·79 for the regional mean. It can be noted that eight of nine hospitals increased both the Ten Steps and Code Global Compliance Scores over time, frequently dramatically (as documented for Hospital F). Examples of actions undertaken at the regional level to address gaps in compliance with Step 4 and other BFHI practices include: adapting training materials, using a regional collaborative approach to discuss challenges identified in the assessments, share strategies and invite champions to present creative solutions. In the case of Hospital F, concrete actions in regard to Step 4 were taken only in 2004 after managers and clinicians forming a breast-feeding committee used monitoring results from the first two assessments to identify areas needing improvement. Changes were introduced gradually, involving all maternity unit staff and aimed at improving nursing competency. These efforts resulted in a doubling of Step 4 Partial Compliance Score between 2001–2004 and 2007 and were instrumental in obtaining BFHI certification before 2007 (personal communication from Hospital F's head nurse and breast-feeding coordinator).

Fig. 6 Global Compliance Scores for the Ten Steps and the Code based on the 1992 BFHI Global Criteria, Montérégie region hospitals, evolution between 2001 and 2007

5. Computerizing assessment tools

In order to avoid time-consuming tasks involved in analysing and reporting assessment results, a computerized tool combining questionnaires and an observation grid for data collection, computations for data analysis and dissemination tables was developed in 2004(Reference Haiek, Gauthier and Brosseau42). The tool was adapted in 2005 to measure Baby-Friendly compliance in the region's nineteen CHC offering pre- and postnatal services. The latest adaptation for a Québec-wide measure in sixty birthing facilities and 147 CHC are the tool's last two bilingual versions(Reference Haiek and Gauthier36, Reference Haiek and Gauthier43). Free copies of the tools are available from the author and may be used under certain copyright and copyleft(44) conditions.

All versions of the tools are available in an Excel file. For example, the BFHI-40 Assessment Tool has fifteen spreadsheets: three introductory sheets three data collection sheets (one per perspective) and nine others, summarizing results. The data collection sheets (rendered fail-safe with several program features) have assigned cells to enter answers/observations, ideally completed by an interviewer using a computer. This procedure results in prompt data computations and graphic representations, performed as data are entered.

Strengths and limitations of the methodology

The methodology's main strength is that it measures compliance based on different sources of information, thus allowing an analysis by triangulation. This is relevant because results are likely to be biased when relying on only one source. Obtaining reports from multiple professionals at each facility and comparing them with maternal answers to similar questions(Reference Rosenberg, Stull and Adler26) and with observations results in a more valid depiction of BFHI compliance(Reference DiGirolamo, Grummer-Strawn and Fein18, Reference Rosenberg, Stull and Adler26). Simple descriptive statistics such as a correlation analysis or dissimilarity index can be used to explore how the sources differ. For example in the 2007 assessment, the largest dissimilarities were between staff/managers and mothers in reports of pre- and postnatal counselling frequency and quality (Steps 3, 5 and 8): according to mothers, staff consistently overestimate compliance but mothers’ reports may be subject to recall bias. In contrast, the lowest dissimilarity between sources lies with indicators assessing policies (Step 1 and the Code) and postpartum follow-up (Step 10), that use observers as one of the sources. In fact, in this particular assessment, observations consistently confirmed staff/managers’ reports. As illustrated above for skin-to-skin contact, reports on hospital routines (Steps 4, 6, 7 and 9) need particular interpretation depending on samples used (e.g. percentage of caesarean deliveries). Ultimately, for an individual hospital, discrepancies between sources need to be interpreted taking into consideration their particular context, sampling procedures, potential biases and, if available, reference data (such as means for a whole country, region or state/province or for BFHI-designated facilities).

Since there seems to be a relationship between the number of steps implemented in a facility and breast-feeding exclusivity(Reference Merten, Dratva and Ackermann-Liebrich10, Reference Declercq, Labbok and Sakala16, 30) and duration(Reference Merten, Dratva and Ackermann-Liebrich10, 15, Reference DiGirolamo, Grummer-Strawn and Fein17, Reference DiGirolamo, Grummer-Strawn and Fein18, Reference Murray25, Reference Rosenberg, Stull and Adler26), the tool's in-depth assessment of all proposed policies and practices(Reference DiGirolamo, Grummer-Strawn and Fein18) may help improve the effectiveness of the BFHI intervention by promoting compliance with all Ten Steps and the Code. Information about other potential institutional- or individual-level confounders(Reference Rosenberg, Stull and Adler26) may be beneficial when analysing and interpreting results. It also provides a rigorous methodology that allows comparability among facilities and reproducibility over time.

Although there is no established gold standard to determine the accuracy of the methodology, it is noteworthy that by 2007 the three hospitals with highest global scores (A, C and F) were those that at the time of the assessment had either already obtained or formally applied for BFHI certification (based on 1992 Global Criteria, those from 2006 had not yet been incorporated into the evaluation process).

In turn, these strengths are related to the methodology's main limitations. The open-ended questions to collect in-depth information require interviewers skilled on breast-feeding and the BFHI. Collecting data from different sources is time-consuming, making it difficult for a given facility to perform detailed observations or obtain large sample sizes, even if sufficient staff and mothers are available to participate. Resulting small sample sizes may hamper representativeness(Reference de Oliveira, Camacho and Tedstone35) or the precision of the estimates, especially when measuring policies and practices with large variation in compliance (i.e. closer to 50 %). For example, Montérégie mothers tend to show more conflicting reports about counselling frequency and quality than about hospital routines, suggesting the need for a larger sample size to assess the former. Furthermore, the fact mothers convey their personal experience that is likely more variable than the generalization managers/staff are asked to report, constitutes another argument to aim for larger sample sizes for mothers. Conversely, when assessments are done on a whole region, province or country, summary or aggregated analyses will improve validity and serve as reference values for individual facilities.

Applications of the measurement methodology

Use of the developed tool is flexible. It can be used to collect data from only one information source or to measure specific steps requiring closer attention. Although developed for planning and monitoring, the methodology may also prove useful for research about BFHI determinants or effectiveness, quality improvement exercises, or as a ‘mock’ practice (or pre-evaluation) in the final stages towards officially becoming Baby-Friendly. In addition, if a country decides to rely fully on a system of internal monitoring, without scheduling external reassessments(Reference Merten, Dratva and Ackermann-Liebrich10, 34), this type of tool could be used to carry out periodic monitoring. Cost in performing a measurement will obviously vary with its use but with more widespread use of personal computers, it is presumably accessible to low-income/low-resource settings.

In fact, because of these user-friendly properties, the interviewer needs only to have basic computer skills. Whether the assessment is performed locally or at regional/provincial level, the main requirement is that interviewers have adequate knowledge of breast-feeding and the BFHI, such as a lactation consultant.

Approximate interviewing time needed to complete a hospital assessment include 20 and 30 min for each staff/manager and mother, respectively. The minimal amount of observation is 1 h but should be increased if observation of mothers/babies is included. To improve validity of the assessment, efforts should be done to avoid sources of selection bias (e.g. announcing the day of the assessment visit or selecting mothers from a list prepared by the hospital) and recall bias. Inevitably, sample size will be influenced by monitoring goals (hospitals alone or CHC also), feasibility and cost. For example, the cost to apply the tool in a small or middle sized hospital (less than 2500 births annually) is a 12 hour-day visit (to interview staff from all shifts). Cost of interviewing mothers will depend on whether done while visiting the facility or by telephone. Other costs to be added are those of training of interviewers (1 d suffices), organizing the visits, travelling time as well as unused time between interviews.

Furthermore, based in our experience, disseminating regional assessments to participating facilities at the local level (via their completed instruments and personalized presentations) not only provides concrete data on achievements and challenges, but also clarifies and demystifies the BFHI recommendations, contributing to the adoption of a ‘regional/local’ common vision. It also seems to spur a mobilization of key players contributing to organizational changes required to progress towards achieving or maintaining the standards required for Baby-Friendly designation. In fact, all eight hospitals and nineteen CHC in the Montérégie have stated in legally mandated local action plans they will seek Baby-Friendly designation or recertificationFootnote * by 2012(45).

Conclusions

It is well recognized that the BFHI is an effective intervention to improve breast-feeding exclusivity and duration. Since its inception in 1991, it has been prioritized in international and national infant feeding policies and recommendations. Still, it remains a challenge to transfer what is already known into action, that is to deliver the intervention to mothers, children and families(Reference Jones, Steketee and Black1). The current paper presents a process for making policies and recommendations targeting the BFHI operational. At a local, regional, provincial, national or international level, measuring BFHI compliance with a computerized tool allows authorities and clinical multidisciplinary teams to set realistic objectives and select appropriate activities to implement the proposed policies and best practices, providing as well valuable baseline or progress information for programme monitoring and evaluation at all levels. Moreover, personalized and timely dissemination of results may help health-care facilities achieve or maintain the international standards required for Baby-Friendly designation.

Acknowledgements

The development of the tool and the 2007 assessment were supported financially by the Agence de la santé et des services sociaux de la Montérégie, where the author worked at the time, and the Ministère de la Santé et des Services sociaux du Québec. There are no competing interests to declare. L.N.H. conceived the different versions of the assessment tools and is first author on all of them. Besides holding the moral rights, L.N.H. also shares the tools’ licence together with the Agence de la santé et des services sociaux de la Montérégie. L.N.H. directed the four studies testing the different versions of the assessment tools, and also wrote the present manuscript. I acknowledge and thank the other authors of the different versions of the assessment tools, Dominique Brosseau, Dany Gauthier and Lydia Rocheleau. I am also grateful to Eric Belzile, Ann Brownlee, Manon Des Côtes, Janie Houle, Ginette Lafontaine, Linda Langlais, Nathalie Lévesque, Monique Michaud, Isabelle Ouellet, François Pilote, Ghislaine Reid and Yue You for their contribution at different stages of this project. Lastly, I would like to thank Jane McCusker, Anne Merewood and Sonia Semenic for revising different versions of the manuscript.