Abstract

Background

Although early, consistent prenatal care (PNC) can be helpful in improving poor birth outcomes, rates of PNC use tend to be lower among African-American women compared to Whites. This study examines low-income African-American women’s perspectives on barriers and facilitators to receiving PNC in an urban setting.

Methods

We conducted six focus groups with 29 women and individual structured interviews with two women. Transcripts were coded to identify barriers and facilitators to obtaining PNC; codes were reviewed to identify emergent themes.

Results

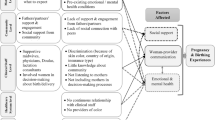

Barriers to obtaining PNC included structural barriers such as transportation and insurance, negative attitudes towards PNC, perceived poor quality of care, unintended pregnancy, and psychosocial stressors such as overall life stress and chaos. Facilitators of PNC included positive experiences such as trusting relationships with providers, respectful staff and providers, and social support.

Conclusions

Findings suggest important components in an ideal PNC model to engage low-income African-American women.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Mathews TJ, MacDorman MF, Thoman EB. Infant mortality statistics from the 2013 period linked birth/infant death data set. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2015;64(9):1–30.

Creanga AA, Berg CJ, Syverson C, Seed K, Bruce FC, Callaghan WM. Pregnancy-related mortality in the United States, 2006–2010. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;125(1):5–12.

King JC. Maternal mortality in the United States—why is it important and what are we doing about it? Semin Perinatol. 2012;36(1):14–8.

Byrd DR, Katcher ML, Peppard P, Durkin M, Remington PL. Infant mortality: explaining black/white disparities in Wisconsin. Matern Child Health J. 2007;11(4):219–326.

Alexander GR, Kotelchuck ML. Assessing the role and effectiveness of prenatal care: history, challenges, and directions for future research. Public Health Rep. 2001;116:306.

Bloch JR, Dawley K, Suplee PD. Application of the Kessner and Kotelchuck prenatal care adequacy indices in a preterm birth population. Public Health Nurs. 2009;26(5):449–59.

Bryant AS, Worjoloh A, Caughey AB, Washington AE. Racial/ethnic disparities in obstetric outcomes and care: prevalence and determinants. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2010;202(4):335–43.

Cox RG, Zhang L, Zotti ME, Graham J. Prenatal care utilization in Mississippi: racial disparities and implications for unfavorable birth outcomes. Matern Child Health J. 2011;15(7):931–42.

Minino AM, Murphy SL. Death in the United States, 2010. NCHS Data Brief. 2012;99:1–8.

Partridge S, Balayla J, Holcroft CA, Abenhaim HA. Inadequate prenatal care utilization and risks of infant mortality and poor birth outcome: a retrospective analysis of 28,729,765 U.S. deliveries over 8 years. Am J Perinatol. 2012;29(10):787–93.

Conway KS, Kutinova A. Maternal health: does prenatal care make a difference? Health Econ. 2006;15(5):461–88.

Cabacungan ET, Ngui EM, McGinley EL. Racial/ethnic disparities in maternal morbidities: a statewide study of labor and delivery hospitalizations in Wisconsin. Matern Child Health J. 2012;16(7):1455–67.

Ngui E, Cortright A, Blair K. An investigation of paternity status and other factors associated with racial and ethnic disparities in birth outcomes in Milwaukee, Wisconsin. Matern Child Health J. 2009;13:467–78.

Johnson AA, Hatcher BJ, El-Khorazaty MN, et al. Determinants of inadequate prenatal care utilization by African American women. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2007;18:620–36.

Chen XK, Wen SW, Yang Q, Walker MC. Adequacy of prenatal care and neonatal mortality in infants born to mothers with and without antenatal high-risk conditions. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol. 2007;47(2):122–7.

Krueger PM, Scholl TO. Adequacy of prenatal care and pregnancy outcome. J Am Osteopath Assoc. 2000;100(8):485–92.

Laditka SB, Laditka JN, Bennett KJ, Probst JC. Delivery complications associated with prenatal care access for Medicaid-insured mothers in rural and urban hospitals. J Rural Health. 2005;21(2):158–66.

Riley L, Stark A. Guidelines for perinatal care. 7th ed. AAP Committee on Fetus and Newborn and ACOG Committee on Obstetric Practice; 2012.

Department of Health & Human Services. Healthy people 2020. 2013.

Alexander GR, Kogan MD, Nabukera S. Racial differences in prenatal care use in the United States: are disparities decreasing? Am J Public Health. 2002;92(12):1970–5.

Frisbie WP, Echevarria S, Hummer RA. Prenatal care utilization among non-Hispanic Whites, African-Americans, and Mexican Americans. Matern Child Health J. 2001;5(1):21–33.

Kogan MD, Kotelchuck M, Johnson S. Racial differences in late prenatal care visits. J Perinatol. 1993;13(1):14–21.

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Health Resources and Services Administration, Maternal and Child Health Bureau. Child health USA 2014. 2014.

Boyatzis RE. Transforming qualitative information: thematic analysis and code development. Thousand Oaks: SAGE; 1998.

Creswell JW. Research design: qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches. 4th ed. Los Angeles: SAGE; 2014.

Rodgers BL, Cowles KV. The qualitative research audit trail: a complex collection of documentation. Res Nurs Health. 1993;16:219–26.

Salm Ward TC, Mazul M, Ngui EM, Bridgewater FD, Harley AE. “You Learn to Go Last”: prenatal care experiences in a sample of low-income African-American women in Milwaukee. Matern Child Health J. 2013;17(10):1753–9.

Sable MR, Stockbauer JW, Schramm WF, Land GH. Differentiating the barriers to adequate prenatal care in Missouri, 1987–88. Public Health Rep. 1990;105(6):549–55.

Kalmuss D, Fennelly K. Barriers to prenatal-care among low-income women in New York City. Fam Plan Perspect. 1990;22(5):215-218-231.

McDonald TP, Coburn AF. Predictors of prenatal-care utilization. Soc Sci Med. 1988;27(2):167–72.

Poland ML, Ager JW, Olson JM. Barriers to receiving adequate prenatal care. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1987;157(2):297–303.

Brown SS. Drawing women into prenatal care. Fam Plan Perspect. 1989;21(2):73–80.

Rosenberg D, Handler A, Rankin KM, Zimbeck M, Adams EK. Prenatal care initiation among very low-income women in the aftermath of welfare reform: does pre-pregnancy Medicaid coverage make a difference? Matern Child Health J. 2007;11(1):11–7.

Cokkinides V, American Cancer Society. Health insurance coverage-enrollment and adequacy of prenatal care utilization. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2001;12(4):461–73.

Lia-Hoagberg B, Rode P, Skovholt CJ, et al. Barriers and motivators to prenatal care among low-income women. Soc Sci Med. 1990;30(4):487–94.

Mikhail B. Prenatal care utilization among low-income African-American women. J Community Health Nurs. 2000;17(4):235–46.

Daniels P, Noe GF, Mayberry R. Barriers to prenatal care among Black women of low socioeconomic status. Am J Health Behav. 2006;30(2):188–98.

Heaman MI, Moffatt M, Elliott L, et al. Barriers, motivators and facilitators related to prenatal care utilization among inner-city women in Winnipeg, Canada. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2014;14:227.

Adams EK, Gavin NI, Benedict MB. Access for pregnant women on Medicaid: variation by race and ethnicity. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2005;16(1):74–95.

Johnson AA, Wesley BD, El-Khorazaty MN, et al. African American and Latino patient versus provider perceptions of determinants of prenatal care initiation. Matern Child Health J. 2011;15 Suppl 1:S27–34.

Krans EE, Davis MM, Palladino CL. Disparate patterns of prenatal care utilization stratified by medical and psychosocial risk. Matern Child Health J. 2013;17:639–45.

Pawasarat J, Quinn LM. Wisconsin’s mass incarceration of African American males: Workforce challenges for 2013. 2013.

Wilson V. Projected decline in unemployment in 2015 won’t lift Blacks out of the recession-carved crater. 2015;393.

Spatial Structures in the Social Sciences, Brown University. US2010 segregation sorting. http://www.s4.brown.edu/us2010/SegSorting/Default.aspx. Updated 2010.

Lori JR, Yi CH, Martyn KK. Provider characteristics desired by African American women in prenatal care. J Transcult Nurs. 2011;22(1):71–6.

Wheatley RR, Kelley MA, Peacock N, Delgado J. Women’s narratives on quality in prenatal care: a multicultural perspective. Qual Health Res. 2008;18(11):1586–98.

Schindler Rising S, Powell Kennedy H, Klima CS. Redesigning prenatal care through CenteringPregnancy. J Midwifery Womens Health. 2004;49(5):398–404.

Krans EE, Davis MM. Strong start for mothers and newborns: implications for prenatal care delivery. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol. 2014;26(6):511–5.

Milligan R, Wingrove BK, Richards L, et al. Perceptions about prenatal care: views of urban vulnerable groups. BMC Public Health. 2002;2:25.

Magriples U, Kershaw TS, Rising SS, Massey Z, Ickovics JR. Prenatal health care beyond the obstetrics service: utilization and predictors of unscheduled care. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2008;198(1):75.e1–7.

Bennett I, Switzer J, Aguirre A, Evans K, Barg F. ‘Breaking it down’: patient-clinician communication and prenatal care among African American women of low and higher literacy. Ann Fam Med. 2006;4(4):334–40.

Fraser MR. Bringing it all together: effective maternal and child health practice as a means to improve public health. Matern Child Health J. 2013;17(5):767–75.

Laditka SB, Laditka JN, Probst JC. Racial and ethnic disparities in potentially avoidable delivery complications among pregnant Medicaid beneficiaries in South Carolina. Matern Child Health J. 2006;10(4):339–50.

Lu MC, Kotelchuck ML, Hogan V, Jones L, Wright K, Halfon N. Closing the Black-White gap in birth outcomes: a life-course approach. Ethn Dis. 2010;20(1 Suppl 2):62–76.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge the generous women who were willing to share their stories with us; Samantha J. Perry, MPH, CHES; Farrin Bridgewater, MA; David Frazer, MPH; and Amy Harley, PhD for their contributions to this project; funding from the Children’s Community Health Plan; and resources from the Center for Urban Population Health and the YWCA of Southeast Wisconsin.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional review board and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Funding

This study was funded in part by Children’s Community Health Plan.

Conflict of Interest

Author A declares that he/she has no conflict of interest. Author B declares that he/she has no conflict of interest. Author C declares that he/she has no conflict of interest.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Mazul, M.C., Salm Ward, T.C. & Ngui, E.M. Anatomy of Good Prenatal Care: Perspectives of Low Income African-American Women on Barriers and Facilitators to Prenatal Care. J. Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities 4, 79–86 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40615-015-0204-x

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40615-015-0204-x