Abstract

Objectives

Neighborhoods characterized by disadvantage influence multiple risk factors for chronic disease and are considered potential drivers of racial and ethnic health inequities in the USA. The objective of the present study was to examine the relationship between neighborhood disadvantage and cumulative biological risk (CBR) and the extent to which the association differs by individual income and education among a large, socioeconomically diverse sample of African American adults.

Methods

Data from the baseline examination of the Jackson Heart Study (2000–2004) were used for the analyses. The sample consisted of African American adults ages 21–85 with complete, geocoded data on CBR biomarkers and behavioral covariates (n = 4410). Neighborhood disadvantage was measured using a composite score of socioeconomic indicators from the 2000 US Census. Eight biomarkers representing cardiovascular, metabolic, inflammatory, and neuroendocrine systems were used to create a CBR score. We fit two-level linear regression models with random intercepts and included cross-level interaction terms between neighborhood disadvantage and individual socioeconomic status (SES).

Results

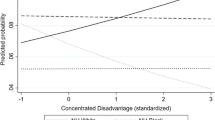

Living in a disadvantaged neighborhood was associated with greater CBR after covariate adjustment (B = 0.18, standard error (SE) 0.07, p < 0.05). Interactions showed a weaker association for individuals with ≤high school education but were not statistically significant.

Conclusion

Disadvantaged neighborhoods contribute to poor health among African American adults via cumulative biological risk. Policies directly addressing the socioeconomic conditions of these environments should be considered as viable options to reduce disease risk in this group and mitigate racial/ethnic health inequities.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Diez-Roux AV, Merkin SS, Arnett D, Chambless L, Massing M, Nieto FJ, et al. Neighborhood of residence and incidence of coronary heart disease. N Engl J Med. 2001;345(2):99–106.

Kawachi I, Subramanian SV. Neighbourhood influences on health. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2007;61(1):3–4.

Krieger N, Chen JT, Waterman PD, Soobader MJ, Subramanian SV, Carson R. Geocoding and monitoring of US socioeconomic inequalities in mortality and cancer incidence: does the choice of area-based measure and geographic level matter?: the public health disparities geocoding project. Am J Epidemiol. 2002;156(5):471–82.

Leal C, Chaix B. The influence of geographic life environments on cardiometabolic risk factors: a systematic review, a methodological assessment and a research agenda. Obes Rev. 2011;12(3):217–30.

Pickett KE, Pearl M. Multilevel analyses of neighbourhood socioeconomic context and health outcomes: a critical review. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2001;55(2):111–22.

Jargowsky P. Stunning progress, hidden problems: the dramatic decline of concentrated poverty in the 1990s: The Brookings Institution; 2003.

Williams DR, Collins C. Racial residential segregation: a fundamental cause of racial disparities in health. Public Health Rep. 2001;116(5):404–16.

Diez-Roux AV. Rev Epidemiol. 2007;55(1):13–21.

Lovasi GS, Hutson MA, Guerra M, Neckerman KM. Built environments and obesity in disadvantaged populations. Epidemiol Rev. 2009;31:7–20.

Morland K, Wing S, Diez Roux A, Poole C. Neighborhood characteristics associated with the location of food stores and food service places. Am J Prev Med. 2002;22(1):23–9.

Powell LM, Slater S, Mirtcheva D, Bao Y, Chaloupka FJ. Food store availability and neighborhood characteristics in the United States. Prev Med. 2007;44(3):189–95.

Sampson RJ, Raudenbush SW, Earls F. Neighborhoods and violent crime: a multilevel study of collective efficacy. Science. 1997;277(5328):918–24.

Ross CE, Mirowsky J. Neighborhood disadvantage, disorder, and health. J Health Soc Behav. 2001;42(3):258–76.

Mujahid MS, Diez Roux AV, Morenoff JD, Raghunathan TE, Cooper RS, Ni H, et al. Neighborhood characteristics and hypertension. Epidemiology. 2008;19(4):590–8.

Kuipers MA, van Poppel MN, van den Brink W, Wingen M, Kunst AE. The association between neighborhood disorder, social cohesion and hazardous alcohol use: a national multilevel study. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2012;126(1–2):27–34.

Slopen N, Dutra LM, Williams DR, Mujahid MS, Lewis TT, Bennett GG, et al. Psychosocial stressors and cigarette smoking among African American adults in midlife. Nicotine Tob Res. 2012;14(10):1161–9.

Cleland V, Ball K, Hume C, Timperio A, King AC, Crawford D. Individual, social and environmental correlates of physical activity among women living in socioeconomically disadvantaged neighbourhoods. Soc Sci Med. 2010;70(12):2011–8.

Wilson PW, D'Agostino RB, Levy D, Belanger AM, Silbershatz H, Kannel WB. Prediction of coronary heart disease using risk factor categories. Circulation. 1998;97(18):1837–47.

Alberti KGMM, Eckel RH, Grundy SM, Zimmet PZ, Cleeman JI, Donato KA, et al. Harmonizing the metabolic syndrome: a joint interim statement of the international diabetes federation task force on epidemiology and prevention; national heart, lung, and blood institute; american heart association; world heart federation; international atherosclerosis society; and international association for the study of obesity. Circulation. 2009;120(16):1640–5.

Crimmins EM, Seeman TE. Integrating biology into the study of health disparities. Popul Dev Rev. 2004;30:89–107.

Seeman TE, McEwen BS, Rowe JW, Singer BH. Allostatic load as a marker of cumulative biological risk: MacArthur studies of successful aging. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98(8):4770–5.

Juster RP, McEwen BS, Lupien SJ. Allostatic load biomarkers of chronic stress and impact on health and cognition. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2010;35(1):2–16.

Bird CE, Seeman T, Escarce JJ, Basurto-Dávila R, Finch BK, Dubowitz T, et al. Neighbourhood socioeconomic status and biological 'wear and tear' in a nationally representative sample of US adults. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2010;64(10):860–5.

Schulz AJ, Mentz G, Lachance L, Johnson J, Gaines C, Israel BA. Associations between socioeconomic status and allostatic load: effects of neighborhood poverty and tests of mediating pathways. Am J Public Health. 2012;102(9):1706–14.

King KE, Morenoff JD, House JS. Neighborhood context and social disparities in cumulative biological risk factors. Psychosom Med. 2011;73(7):572–9.

Merkin SS, Basurto-Dávila R, Karlamangla A, Bird CE, Lurie N, Escarce J, et al. Neighborhoods and cumulative biological risk profiles by race/ethnicity in a national sample of U.S. adults: NHANES III. Ann Epidemiol. 2009;19(3):194–201.

Osypuk TL, Galea S, McArdle N, Acevedo-Garcia D. Quantifying separate and unequal: racial-ethnic distributions of neighborhood poverty in metropolitan America. Urban Aff Rev Thousand Oaks Calif. 2009;45(1):25–65.

U.S. Census Bureau. Current Population Reports, P60-213, Money Income in the United States: 2000, U.S. Government Printing Office, Washington, DC, 2001.

U.S. Census Bureau. 2010 Census Special Reports, Patterns of Metropolitan and Micropolitan Population Change: 2000 to 2010, C2010SR-01, U.S. Government Printing Office, Washington, DC, 2012.

Centers for Disease Control. Adult Obesity Facts; 2013. Retrieved February 9, 2014, from http://www.cdc.gov/obesity/data/adult.html.

National Institutes of Health. Morbidity and mortality: 2012 chart book on cardiovascular, lung and blood diseases; 2012.

Robinson JC, Wyatt SB, Hickson D, Gwinn D, Faruque F, Sims M, et al. Methods for retrospective geocoding in population studies: the Jackson heart study. J Urban Health. 2010;87(1):136–50.

Fuqua SR, Wyatt SB, Andrew ME, Sarpong DF, Henderson FR, Cunningham MF, et al. Recruiting African-american research participation in the Jackson heart study: methods, response rates, and sample description. Ethn Dis. 2005;15(4 Suppl 6):S6-18–29.

Carpenter MA, Crow R, Steffes M, Rock W, Heilbraun J, Evans G, et al. Laboratory, reading center, and coordinating center data management methods in the Jackson heart study. Am J Med Sci. 2004;328(3):131–44.

Payne TJ, Wyatt SB, Mosley TH, Dubbert PM, Guiterrez-Mohammed ML, Calvin RL, et al. Sociocultural methods in the Jackson heart study: conceptual and descriptive overview. Ethn Dis. 2005;15(4 Suppl 6):S6-38–48.

Taylor HA, Wilson JG, Jones DW, Sarpong DF, Srinivasan A, Garrison RJ, et al. Toward resolution of cardiovascular health disparities in African americans: design and methods of the Jackson heart study. Ethn Dis. 2005;15(4 Suppl 6):S6. -4-17.

Clark CR, Ommerborn MJ, Hickson DA, Grooms KN, Sims M, Taylor HA, et al. Neighborhood disadvantage, neighborhood safety and cardiometabolic risk factors in African americans: biosocial associations in the Jackson heart study. PLoS One. 2013;8(5):1–10.

Diez-Roux AV, Kiefe CI, Jacobs Jr DR, Haan M, Jackson SA, Nieto FJ, et al. Area characteristics and individual-level socioeconomic position indicators in three population-based epidemiologic studies. Ann Epidemiol. 2001;11(6):395–405.

Hickson DA, Diez Roux AV, Gebreab SY, Wyatt SB, Dubbert PM, Sarpong DF, et al. Social patterning of cumulative biological risk by education and income among African americans. Am J Public Health. 2012;102(7):1362–9.

Seeman T, Epel E, Gruenewald T, Karlamangla A, McEwen BS. Socio-economic differentials in peripheral biology: cumulative allostatic load. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2010;1186:223–39.

Smitherman TA, Dubbert PM, Grothe KB, Sung JH, Kendzor DE, Reis JP, et al. Validation of the Jackson heart study physical activity survey in African americans. J Phys Act Health. 2009;6(1):S124–32.

Carithers TC, Talegawkar SA, Rowser ML, Henry OR, Dubbert PM, Bogle ML, et al. Validity and calibration of food frequency questionnaires used with African-american adults in the Jackson heart study. J Am Diet Assoc. 2009;109(7):1184–93.

Singer J, Using SAS. PROC MIXED to fit multilevel models, hierarchical models, and individual growth models. J Educ Behav Stat. 1998;24(4):323–55.

Diez-Roux AV, Jacobs DR, Kiefe CI, Study CARDiYAC. Neighborhood characteristics and components of the insulin resistance syndrome in young adults: the coronary artery risk development in young adults (CARDIA) study. Diabetes Care. 2002;25(11):1976–82.

Diez-Roux AV, Nieto FJ, Muntaner C, Tyroler HA, Comstock GW, Shahar E, et al. Neighborhood environments and coronary heart disease: a multilevel analysis. Am J Epidemiol. 1997;146(1):48–63.

Stalder T, Kirschbaum C. Analysis of cortisol in hair--state of the art and future directions. Brain Behav Immun. 2012;26(7):1019–29.

Wilson J. The Truly Disadvantage: the inner city, the underclass and social policy: University of Chicago Press; 1987.

Pattillo M. Black middle-class neighborhoods. Annu Rev Sociol. 2005;31:305–29.

Jackson PB, Williams DR. The intersection of race, gender, and SES, health paradoxes. In: Mullings' Sa, editor. Gender, race, class, and health: Intersectional Approaches: Jossey-Bass; 2006. p. 131–162.

Charles CZ. The dynamics of racial residential segregation. Annu Rev Sociol. 2003;29:167–207.

Turner MA, Ross SL, Galster GC, Yinger J. Discrimination in metropoltian housing markets: phase I. Washington: US Department of Housing and Urban Development; 2002.

Briggs X, Benjamin KJ. Has exposure to poor neighborhoods changed in America? Race, risk and housing locations in two decades. Urban Stud. 2009;46:429–53.

Crowder K, South S. Race. class, and changing patterns of migration between poor and nonpoor neighborhoods. Am J Sociol. 2005;110(6):1751–63.

South S, Pais J, Crowder K. Metropolitan influences on migration to poor and nonpoor neighborhoods. Soc Sci Res. 2011;40(3):950–64.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by funding from the National Institutes of Health National Research Service Award training grant, CVD Epidemiology Training Program in Behavior, the Environment and Global Health (T32 HL 098048–02), and the NIH Initiative to Maximize Student Diversity grant funding. Special thanks to the JHS research staff and study participants.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

This research was supported by funding from the National Institutes of Health National Research Service Award training grant, CVD Epidemiology Training Program in Behavior, the Environment and Global Health (T32 HL 098048–02), and the NIH Initiative to Maximize Student Diversity grant funding.

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed consent was obtained from all participants included in the JHS, and the study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Boards of Tougaloo College and the University of Mississippi Medical Center. Secondary data analyses conducted in this study was approved by the Harvard School of Public Health Institutional Review Board.

Conflict of Interest

Dr. Barber, Dr. Hickson, Dr. Kawachi, Dr. Subramanian, and Dr. Earls declare that they have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Barber, S., Hickson, D.A., Kawachi, I. et al. Neighborhood Disadvantage and Cumulative Biological Risk Among a Socioeconomically Diverse Sample of African American Adults: An Examination in the Jackson Heart Study. J. Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities 3, 444–456 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40615-015-0157-0

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40615-015-0157-0