Abstract

Purpose of Review

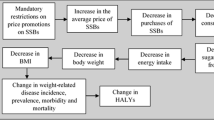

The price of foods and beverages is a critical driver of food choice, particularly among families and households with limited food budgets. Policies targeting unhealthy food and beverage price promotions represent an untapped policy target for improving population diets and health. Here we review policy options for reducing the frequency and influence of price promotions on unhealthy foods and beverages (high in one or more of salt, sugar and saturated fat), and demonstrate their potential to complement other food policies and improve population diets.

Recent Findings

Price promotions on unhealthy foods and beverages are ubiquitous in many settings globally and appear to be more common than price promotions for healthy food. Shoppers appear to be more responsive to price promotions on unhealthy foods and beverages compared to price promotions for healthier items, with evidence that discounts lead to impulse purchases, stockpiling and overconsumption. A range of policy options exist to reduce the influence of price promotions on unhealthy foods and beverages, but none have been tested in the real world, meaning the industry and consumer responses to such policies are unclear.

Summary

Policies that reduce the prevalence and influence of unhealthy food and beverage price promotions should be considered as part of a comprehensive approach to improving population diets.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Papers of particular interest, published recently, have been highlighted as: • Of importance •• Of major importance

Forouzanfar MH, Alexander L, Anderson HR, Bachman VF, Biryukov S, Brauer M, et al. Global, regional, and national comparative risk assessment of 79 behavioural, environmental and occupational, and metabolic risks or clusters of risks in 188 countries, 1990–2013: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013. Lancet. 2015;386(10010):2287–323.

Collaborators GBDD. Health effects of dietary risks in 195 countries, 1990-2017: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2017. Lancet. 2019. May 11; 393(10184):1958–1972.

Micha R, Penalvo JL, Cudhea F, Imamura F, Rehm CD, Mozaffarian D. Association between dietary factors and mortality from heart disease, stroke, and type 2 diabetes in the United States. JAMA. 2017;317(9):912–24.

World Health Organization. Healthy diets key facts Geneva. 2018 [available from: https://www.who.int/en/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/healthy-diet. Accessed 15 April 2019.

Price Waterhouse Coopers. Weighing the cost of obesity: A case for action. 2015. Available from: https://www.pwc.com.au/publications/healthcare-obesity.html. Accessed 15 April 2019.

Finkelstein EA, Trogdon JG, Cohen JW, Dietz W. Annual medical spending attributable to obesity: payer-and service-specific estimates. Health Aff (Millwood). 2009;28(5):w822–31.

Trogdon JG, Finkelstein EA, Hylands T, Dellea PS, Kamal-Bahl SJ. Indirect costs of obesity: a review of the current literature. Obes Rev. 2008;9(5):489–500.

OECD. Obesity and the economics of prevention. Paris: OECD Publishing; 2010.

World Health Organisation. Using price policies to promote healthier diets. 2015.

Zorbas C, Palermo C, Chung A, Iguacel I, Peeters A, Bennett R, et al. Factors perceived to influence healthy eating: a systematic review and meta-ethnographic synthesis of the literature. Nutr Rev. 2018;76(12):861–74.

Brimblecombe J, Ferguson M, Chatfield MD, Liberato SC, Gunther A, Ball K, et al. Effect of a price discount and consumer education strategy on food and beverage purchases in remote indigenous Australia: a stepped-wedge randomised controlled trial. Lancet Public Health. 2017;2(2):e82–95.

Ball K, McNaughton SA, Le HN, Gold L, Ni Mhurchu C, Abbott G, et al. Influence of price discounts and skill-building strategies on purchase and consumption of healthy food and beverages: outcomes of the supermarket healthy eating for life randomized controlled trial. Am J Clin Nutr. 2015;101(5):1055–64.

Taillie LS, Rivera JA, Popkin BM, Batis C. Do high vs. low purchasers respond differently to a nonessential energy-dense food tax? Two-year evaluation of Mexico’s 8% nonessential food tax. Prev Med. 2017;105S:S37–42.

Backholer K, Vandevijvere S, Blake M, Tseng M. Sugar-sweetened beverage taxes in 2018: a year of reflections and consolidation. Public Health Nutr. 2018 Dec;21(18):3291–3295.

Scottish Government. A Healthier Future: Scotland’s Diet & Healthy Weight Delivery Plan. 2018. Available at http://www.gov.scot/Publications/2018/07/8833. Accessed 15 April 2019.

Hawkes C. Sales promotions and food consumption. Nutr Rev. 2009;67(6):333–42.

Analytics N. Promotions not so special anymore. 2014. Available from: https://www.nielsen.com/au/en/insights/news/2014/promotions-not-so-special-anymore.html.

•• Riesenberg D, Backholer K, Zorbas C, Sacks G, Paix A, Marshall J, et al. Frequency and magnitude of price promotions on Australian supermarket food according to food category and product healthiness. Am J Public Health. 2019; In Press. One of the few studies that comprehensively described the prevalence (and depth of discount) of unhealthy food price promotiosn over 12 months.

•• Zorbas C, Gillham B, Blake M, Boeleson-Robbinson T, Peeters A, Cameron AJ, et al. Monitoring price promotions for all beverages sold within Australian supermarkets. Aust N Z J Public Health. 2019 Jun 10. https://doi.org/10.1111/1753-6405.12899 The only study that tracks the weekly price promotion cycle ver 12 months to describe price promotiosn for all beverages in Australia.

•• Smithson M, Kirk J, Capelin C. Sugar reduction: the evidence for action Annexe 4: An analysis of the role of price promotions on the household purchases of food and drinks high in sugar. A research project for Public Health England conducted by Kantar Worldpanel. London. October 2015. Available from: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/470175/Annexe_4._Analysis_of_price_promotions.pdf. Accessed 15 April 2019. Describes the case for policy action to reduce the influence of high-sugar price promotions in the UK.

Chandon P, Wansink B. When are stockpiled products consumed faster? A convenience–salience framework of postpurchase consumption incidence and quantity. J Mark Res. 2002;39(3):321–35.

Jensen RT, Miller NH. Giffen behavior and subsistence consumption. Am Econ Rev. 2008;98(4):1553–77.

Finkelstein SR, Fishbach A. When healthy food makes you hungry. J Consum Res. 2010;37(3):357–67.

Talukdar D, Lindsey C. To buy or not to buy: consumers’ demand response patterns for healthy versus unhealthy food. J Mark. 2013;77:124–38.

•• Coker. T, Rumgay. H, Whiteside. E, Rosenberg. G, Vohra. J. Paying the price. New evidence on the link between price promotions, purchasing of less healthy food and drink, and overweight and obesity in Great Britain. Cancer Research UK. 2019. Available from: https://www.cancerresearchuk.org/sites/default/files/paying_the_price_-_exec_summary.pdf. Accessed 15 April 2019. The most comprehensive study to date to describe the influence of price promotions on sonsumer behaviour and the implications for health.

• Taillie LS, Ng SW, Xue Y, Harding M. Deal or no deal? The prevalence and nutritional quality of price promotions among U.S. food and beverage purchases. Appetite. 2017;117:365–72. One of the few studies examining the difference in the purchasing behaviour for healthy and less healthy food and beverage price promotions in in the USA.

• Nakamura R, Suhrcke M, Jebb SA, Pechey R, Almiron-Roig E, Marteau TM. Price promotions on healthier compared with less healthy foods: a hierarchical regression analysis of the impact on sales and social patterning of responses to promotions in Great Britain. Am J Clin Nutr. 2015;101(4):808–16. One of the few studies examining the difference in the purchasing behaviour for healthy and less healthy food and beverage price promotions in in the UK.

UK Government. Restricting promotions of products high in fat, sugar and salt by location and by price London, UK: Department of Health and Social Care; 2019 [Available from: https://consultations.dh.gov.uk/obesity/2efb8c9f/. Accessed 15 April 2019.

Scottish Government. Reducing health harms of foods high in fat, sugar or salt: consultation Edinburgh, Scotland: Population Health Directorate; 2018 [Available from: https://www.gov.scot/publications/reducing-health-harms-foods-high-fat-sugar-salt/. Accessed 15 April 2019.

Jones A, Shahid M, Neal B. Uptake of Australia’s health star rating system. Nutrients. 2018; Jul 30;10(8).https://doi.org/10.3390/nu10080997.

Julia C, Hercberg S. Big Food’s opposition to the French nutri-score front-of-pack labeling warrants a global reaction. Am J Public Health. 2018;108(3):318–20.

Chapman S, Wakefield M. Tobacco control advocacy in Australia: reflections on 30 years of progress. Health Educ Behav. 2001;28(3):274–89.

Chapman S. Tobacco giant wants to eliminate smoking. BMJ. 2017;358:j4443.

Veerman L. The impact of sugared drink taxation and industry response. Lancet Public Health. 2017;2(1):e2–3.

Onagan FCC, Ho BLC, Chua KKT. Development of a sweetened beverage tax, Philippines. Bull World Health Organ. 2019;97(2):154–9.

Lawrence M, Woods J, Pollard C. The significant influence of ‘Big Food’ over the design and implementation of the health star rating system. Nutr Diet. 2019;76(1):118.

Nakamura R, Suhrcke M, Pechey R, Morciano M, Roland M, Marteau TM. Impact on alcohol purchasing of a ban on multi-buy promotions: a quasi-experimental evaluation comparing Scotland with England and Wales. Addiction. 2014;109(4):558–67.

Wirfalt AK, Jeffery RW. Using cluster analysis to examine dietary patterns: nutrient intakes, gender, and weight status differ across food pattern clusters. J Am Diet Assoc. 1997;97(3):272–9.

WatsonWL, LauV,Wellard L, Hughes C, ChapmanK. Advertising to children initiatives have not reduced unhealthy food advertising on Australian television. J Public Health (Oxf). 2017;39(4):787–92.

Acknowledgements

KB and GS were supported by a Heart Foundation Future Leader Fellowship (102047, 102035) from the National Heart Foundation of Australia. AJC and GS were the recipients of Australian Research Council Discovery Early Career Researcher Awards (project numbers DE160100141 and DE160100307). GS is a researcher within a NHMRC Centre for Research Excellence entitled Reducing Salt Intake Using Food Policy Interventions (APP1117300). AJC and GS are researchers in a NHMRC Centre of Research Excellence in Food Retail Environments for Health (APP1152968).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

Kathryn Backholer, Gary Sacks and Adrian J. Cameron declare they have no conflict of interest.

Human and Animal Rights and Informed Consent

This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

This article is part of the Topical Collection on Public Health Nutrition

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Backholer, K., Sacks, G. & Cameron, A.J. Food and Beverage Price Promotions: an Untapped Policy Target for Improving Population Diets and Health. Curr Nutr Rep 8, 250–255 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13668-019-00287-z

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13668-019-00287-z