Abstract

Purpose

We report a female infant identified by newborn screening for severe combined immunodeficiencies (NBS SCID) with T cell lymphopenia (TCL). The patient had persistently elevated alpha-fetoprotein (AFP) with IgA deficiency, and elevated IgM. Gene sequencing for a SCID panel was uninformative. We sought to determine the cause of the immunodeficiency in this infant.

Methods

We performed whole-exome sequencing (WES) on the patient and parents to identify a genetic diagnosis. Based on the WES result, we developed a novel flow cytometric panel for rapid assessment of DNA repair defects using blood samples. We also performed whole transcriptome sequencing (WTS) on fibroblast RNA from the patient and father for abnormal transcript analysis.

Results

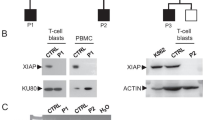

WES revealed a pathogenic paternally inherited indel in ATM. We used the flow panel to assess several proteins in the DNA repair pathway in lymphocyte subsets. The patient had absent phosphorylation of ATM, resulting in absent or aberrant phosphorylation of downstream proteins, including γH2AX. However, ataxia-telangiectasia (AT) is an autosomal recessive condition, and the abnormal functional data did not correspond with a single ATM variant. WTS revealed in-frame reciprocal fusion transcripts involving ATM and SLC35F2 indicating a chromosome 11 inversion within 11q22.3, of maternal origin. Inversion breakpoints were identified within ATM intron 16 and SLC35F2 intron 7.

Conclusions

We identified a novel ATM-breaking chromosome 11 inversion in trans with a pathogenic indel (compound heterozygote) resulting in non-functional ATM protein, consistent with a diagnosis of AT. Utilization of several molecular and functional assays allowed successful resolution of this case.

Similar content being viewed by others

Abbreviations

- NBS SCID:

-

Newborn screening for severe combined immunodeficiencies

- WES:

-

Whole exome sequencing

- WTS:

-

Whole transcriptome sequencing

- PID:

-

Primary immunodeficiency

- TCL:

-

T cell lymphopenia

- XCIND:

-

X-ray (irradiation sensitivity), cancer susceptibility, immunodeficiency, neurological involvement and double-strand DNA breakage

- AT:

-

Ataxia-telangiectasia

- HCT:

-

Hematopoietic cell transplantation

- TCR:

-

T-cell receptor

- DSB:

-

Double-strand break

- IVIG:

-

Intravenous immunoglobulin

- AFP:

-

Alpha-fetoprotein

- URTIs:

-

Upper respiratory tract infections

- UTIs:

-

Urinary tract infections

- gnomAD:

-

Genome Aggregation Database

- LOF:

-

Loss-of-function

- HDR:

-

Homology-directed repair

- NHEJ:

-

Non-homologous end-joining

- MFI:

-

Mean fluorescence intensity

- NGS:

-

Next-generation sequencing

- TCGA:

-

The Cancer Genome Atlas

References

Chan A, Scalchunes C, Boyle M, Puck JM. Early vs. delayed diagnosis of severe combined immunodeficiency: a family perspective survey. Clin Immunol. 2011;138(1):3–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clim.2010.09.010.

Chase NM, Verbsky JW, Routes JM. Newborn screening for T-cell deficiency. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol. 2010;10(6):521–5. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACI.0b013e32833fd6fe.

Dorsey M, Puck J. Newborn screening for severe combined immunodeficiency in the US: current status and approach to management. Int J Neonatal Screen. 2017;3(2):15.

Kwan A, Abraham RS, Currier R, Brower A, Andruszewski K, Abbott JK, et al. Newborn screening for severe combined immunodeficiency in 11 screening programs in the United States. JAMA. 2014;312(7):729–38. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2014.9132.

Mallott J, Kwan A, Church J, Gonzalez-Espinosa D, Lorey F, Tang LF, et al. Newborn screening for SCID identifies patients with ataxia telangiectasia. J Clin Immunol. 2013;33(3):540–9. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10875-012-9846-1.

Shearer WT, Dunn E, Notarangelo LD, Dvorak CC, Puck JM, Logan BR, et al. Establishing diagnostic criteria for severe combined immunodeficiency disease (SCID), leaky SCID, and Omenn syndrome: the primary immune deficiency treatment consortium experience. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2014;133(4):1092–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaci.2013.09.044.

Patel DR, Yu H, Wong LC, Lupski JR, Seeborg FO, Rider NL, et al. Linking newborn severe combined immunodeficiency screening with targeted exome sequencing: a case report. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2017;5(5):1442–4. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaip.2017.03.004.

Meyts I, Bosch B, Bolze A, Boisson B, Itan Y, Belkadi A, et al. Exome and genome sequencing for inborn errors of immunity. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2016;138(4):957–69. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaci.2016.08.003.

Stray-Pedersen A, Sorte HS, Samarakoon P, Gambin T, Chinn IK, Akdemir ZHC, et al. Primary immunodeficiency diseases: genomic approaches delineate heterogeneous Mendelian disorders. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2017;139(1):232–45. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaci.2016.05.042.

Cummings BB, Marshall JL, Tukiainen T, Lek M, Donkervoort S, Foley AR et al. Improving genetic diagnosis in Mendelian disease with transcriptome sequencing. Sci Transl Med. 2017;9(386). https://doi.org/10.1126/scitranslmed.aal5209.

Kremer LS, Bader DM, Mertes C, Kopajtich R, Pichler G, Iuso A, et al. Genetic diagnosis of Mendelian disorders via RNA sequencing. Nat Commun. 2017;8:15824. https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms15824.

Griffith LM, Cowan MJ, Notarangelo LD, Kohn DB, Puck JM, Shearer WT, et al. Primary immune deficiency treatment consortium (PIDTC) update. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2016;138(2):375–85. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaci.2016.01.051.

Grunebaum E, Mazzolari E, Porta F, Dallera D, Atkinson A, Reid B, et al. Bone marrow transplantation for severe combined immune deficiency. JAMA. 2006;295(5):508–18. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.295.5.508.

Hagin D, Burroughs L, Torgerson TR. Hematopoietic stem cell transplant for immune deficiency and immune dysregulation disorders. Immunol Allergy Clin N Am. 2015;35(4):695–711. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iac.2015.07.010.

Cowan MJ, Gennery AR. Radiation-sensitive severe combined immunodeficiency: the arguments for and against conditioning before hematopoietic cell transplantation—what to do? J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2015;136(5):1178–85. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaci.2015.04.027.

Veys P. Reduced intensity transplantation for primary immunodeficiency disorders. Immunol Allergy Clin N Am. 2010;30(1):103–24. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iac.2009.11.003.

van Os NJH, Jansen AFM, van Deuren M, Haraldsson A, van Driel NTM, Etzioni A, et al. Ataxia-telangiectasia: immunodeficiency and survival. Clin Immunol. 2017;178:45–55. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clim.2017.01.009.

Boultwood J. Ataxia telangiectasia gene mutations in leukaemia and lymphoma. J Clin Pathol. 2001;54(7):512–6.

Chun HH, Gatti RA. Ataxia-telangiectasia, an evolving phenotype. DNA repair. 2004;3(8–9):1187–96. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dnarep.2004.04.010.

Gatti R, Perlman S. Ataxia-telangiectasia. In: Adam MP, Ardinger HH, Pagon RA, Wallace SE, Bean LJH, Mefford HC et al. (eds). GeneReviews(R). Seattle: University of Washington, Seattle. GeneReviews is a registered trademark of the University of Washington, Seattle. All rights reserved; 1993.

Lavin M. Role of the ataxia-telangiectasia gene (ATM) in breast cancer. A-T heterozygotes seem to have an increased risk but its size is unknown. BMJ (Clin Res Ed). 1998;317(7157):486–7.

Swift M, Morrell D, Massey RB, Chase CL. Incidence of cancer in 161 families affected by ataxia-telangiectasia. N Engl J Med. 1991;325(26):1831–6. https://doi.org/10.1056/nejm199112263252602.

Lavin MF, Gueven N, Bottle S, Gatti RA. Current and potential therapeutic strategies for the treatment of ataxia-telangiectasia. Br Med Bull. 2007;81–82:129–47. https://doi.org/10.1093/bmb/ldm012.

Slack J, Albert MH, Balashov D, Belohradsky BH, Bertaina A, Bleesing J, et al. Outcome of hematopoietic cell transplantation for DNA double-strand break repair disorders. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2018;141(1):322–8 e10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaci.2017.02.036.

Beier R, Sykora KW, Woessmann W, Maecker-Kolhoff B, Sauer M, Kreipe HH, et al. Allogeneic-matched sibling stem cell transplantation in a 13-year-old boy with ataxia telangiectasia and EBV-positive non-Hodgkin lymphoma. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2016;51(9):1271–4. https://doi.org/10.1038/bmt.2016.93.

Ghosh S, Schuster FR, Binder V, Niehues T, Baldus SE, Seiffert P, et al. Fatal outcome despite full lympho-hematopoietic reconstitution after allogeneic stem cell transplantation in atypical ataxia telangiectasia. J Clin Immunol. 2012;32(3):438–40. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10875-012-9654-7.

Staples ER, McDermott EM, Reiman A, Byrd PJ, Ritchie S, Taylor AM, et al. Immunodeficiency in ataxia telangiectasia is correlated strongly with the presence of two null mutations in the ataxia telangiectasia mutated gene. Clin Exp Immunol. 2008;153(2):214–20. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2249.2008.03684.x.

Asmann YW, Middha S, Hossain A, Baheti S, Li Y, Chai HS, et al. TREAT: a bioinformatics tool for variant annotations and visualizations in targeted and exome sequencing data. Bioinformatics. 2012;28(2):277–8. https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/btr612.

Kalari KR, Nair AA, Bhavsar JD, O'Brien DR, Davila JI, Bockol MA, et al. MAP-RSeq: Mayo analysis pipeline for RNA sequencing. BMC Bioinformatics. 2014;15:224. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2105-15-224.

Stray-Pedersen A, Borresen-Dale AL, Paus E, Lindman CR, Burgers T, Abrahamsen TG. Alpha fetoprotein is increasing with age in ataxia-telangiectasia. Eur J Paediatr Neurol. 2007;11(6):375–80. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejpn.2007.04.001.

Noordzij JG, Wulffraat NM, Haraldsson A, Meyts I, van’t Veer LJ, Hogervorst FB, et al. Ataxia-telangiectasia patients presenting with hyper-IgM syndrome. Arch Dis Child. 2009;94(6):448–9. https://doi.org/10.1136/adc.2008.149351.

Richards S, Aziz N, Bale S, Bick D, Das S, Gastier-Foster J, et al. Standards and guidelines for the interpretation of sequence variants: a joint consensus recommendation of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics and the Association for Molecular Pathology. Genet Med. 2015;17(5):405–24. https://doi.org/10.1038/gim.2015.30.

Telatar M, Teraoka S, Wang Z, Chun HH, Liang T, Castellvi-Bel S, et al. Ataxia-telangiectasia: identification and detection of founder-effect mutations in the ATM gene in ethnic populations. Am J Hum Genet. 1998;62(1):86–97. https://doi.org/10.1086/301673.

Laake K, Jansen L, Hahnemann JM, Brondum-Nielsen K, Lonnqvist T, Kaariainen H, et al. Characterization of ATM mutations in 41 Nordic families with ataxia telangiectasia. Hum Mutat. 2000;16(3):232–46. https://doi.org/10.1002/1098-1004(200009)16:3<232::aid-humu6>3.0.co;2-l.

Laake K, Telatar M, Geitvik GA, Hansen RO, Heiberg A, Andresen AM, et al. Identical mutation in 55% of the ATM alleles in 11 Norwegian AT families: evidence for a founder effect. Eur J Hum Genet. 1998;6(3):235–44. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.ejhg.5200181.

Du L, Lai CH, Concannon P, Gatti RA. Rapid screen for truncating ATM mutations by PTT-ELISA. Mutat Res. 2008;640(1–2):139–44. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mrfmmm.2008.01.002.

Paull TT. Mechanisms of ATM activation. Annu Rev Biochem. 2015;84:711–38. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-biochem-060614-034335.

Panier S, Boulton SJ. Double-strand break repair: 53BP1 comes into focus. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2014;15(1):7–18. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrm3719.

Kuo LJ, Yang LX. Gamma-H2AX—a novel biomarker for DNA double-strand breaks. In vivo (Athens, Greece). 2008;22(3):305–9.

Mauracher AA, Pagliarulo F, Faes L, Vavassori S, Gungor T, Bachmann LM, et al. Causes of low neonatal T-cell receptor excision circles: a systematic review. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2017;5(5):1457–60.e22. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaip.2017.02.009.

Bakkenist CJ, Kastan MB. DNA damage activates ATM through intermolecular autophosphorylation and dimer dissociation. Nature. 2003;421(6922):499–506. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature01368.

Bensimon A, Schmidt A, Ziv Y, Elkon R, Wang SY, Chen DJ, et al. ATM-dependent and -independent dynamics of the nuclear phosphoproteome after DNA damage. Sci Signal. 2010;3(151):rs3. https://doi.org/10.1126/scisignal.2001034.

Kozlov SV, Graham ME, Peng C, Chen P, Robinson PJ, Lavin MF. Involvement of novel autophosphorylation sites in ATM activation. EMBO J. 2006;25(15):3504–14. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.emboj.7601231.

Kastan MB, Lim DS. The many substrates and functions of ATM. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2000;1(3):179–86. https://doi.org/10.1038/35043058.

Ismail IH, Wadhra TI, Hammarsten O. An optimized method for detecting gamma-H2AX in blood cells reveals a significant interindividual variation in the gamma-H2AX response among humans. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35(5):e36. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkl1169.

Nahas SA, Butch AW, Du L, Gatti RA. Rapid flow cytometry-based structural maintenance of chromosomes 1 (SMC1) phosphorylation assay for identification of ataxia-telangiectasia homozygotes and heterozygotes. Clin Chem. 2009;55(3):463–72. https://doi.org/10.1373/clinchem.2008.107128.

Porcedda P, Turinetto V, Brusco A, Cavalieri S, Lantelme E, Orlando L, et al. A rapid flow cytometry test based on histone H2AX phosphorylation for the sensitive and specific diagnosis of ataxia telangiectasia. Cytometry A J Int Soc Analyt Cytol. 2008;73(6):508–16. https://doi.org/10.1002/cyto.a.20566.

Exley AR, Buckenham S, Hodges E, Hallam R, Byrd P, Last J, et al. Premature ageing of the immune system underlies immunodeficiency in ataxia telangiectasia. Clin Immunol. 2011;140(1):26–36. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clim.2011.03.007.

Verhagen MM, Last JI, Hogervorst FB, Smeets DF, Roeleveld N, Verheijen F, et al. Presence of ATM protein and residual kinase activity correlates with the phenotype in ataxia-telangiectasia: a genotype-phenotype study. Hum Mutat. 2012;33(3):561–71. https://doi.org/10.1002/humu.22016.

Yu H, Zhang VW, Stray-Pedersen A, Hanson IC, Forbes LR, de la Morena MT, et al. Rapid molecular diagnostics of severe primary immunodeficiency determined by using targeted next-generation sequencing. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2016;138(4):1142–51.e2. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaci.2016.05.035.

Bucciol G, Van Nieuwenhove E, Moens L, Itan Y, Meyts I. Whole exome sequencing in inborn errors of immunity: use the power but mind the limits. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol. 2017;17(6):421–30. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACI.0000000000000398.

Retterer K, Juusola J, Cho MT, Vitazka P, Millan F, Gibellini F, et al. Clinical application of whole-exome sequencing across clinical indications. Genet Med Off J Am Coll Med Genet. 2016;18(7):696–704. https://doi.org/10.1038/gim.2015.148.

Suzuki T, Tsurusaki Y, Nakashima M, Miyake N, Saitsu H, Takeda S, et al. Precise detection of chromosomal translocation or inversion breakpoints by whole-genome sequencing. J Hum Genet. 2014;59(12):649–54. https://doi.org/10.1038/jhg.2014.88.

Yuen RK, Thiruvahindrapuram B, Merico D, Walker S, Tammimies K, Hoang N, et al. Whole-genome sequencing of quartet families with autism spectrum disorder. Nat Med. 2015;21(2):185–91. https://doi.org/10.1038/nm.3792.

Blake J, Riddell A, Theiss S, Gonzalez AP, Haase B, Jauch A, et al. Sequencing of a patient with balanced chromosome abnormalities and neurodevelopmental disease identifies disruption of multiple high risk loci by structural variation. PLoS One. 2014;9(3):e90894. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0090894.

Kanegane H, Hoshino A, Okano T, Yasumi T, Wada T, Takada H, et al. Flow cytometry-based diagnosis of primary immunodeficiency diseases. Allergol Int Off J Japan Soc Allergol. 2017;67:43–54. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.alit.2017.06.003.

Abraham RS, Aubert G. Flow cytometry, a versatile tool for diagnosis and monitoring of primary immunodeficiencies. Clin Vaccine Immunol. 2016;23(4):254–71. https://doi.org/10.1128/cvi.00001-16.

van Schouwenburg PA, Davenport EE, Kienzler AK, Marwah I, Wright B, Lucas M, et al. Application of whole genome and RNA sequencing to investigate the genomic landscape of common variable immunodeficiency disorders. Clin Immunol. 2015;160(2):301–14. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clim.2015.05.020.

Borte S, Celiksoy MH, Menzel V, Ozkaya O, Ozen FZ, Hammarstrom L, et al. Novel NLRP12 mutations associated with intestinal amyloidosis in a patient diagnosed with common variable immunodeficiency. Clin Immunol. 2014;154(2):105–11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clim.2014.07.003.

Teixeira VH, Olaso R, Martin-Magniette ML, Lasbleiz S, Jacq L, Oliveira CR, et al. Transcriptome analysis describing new immunity and defense genes in peripheral blood mononuclear cells of rheumatoid arthritis patients. PLoS One. 2009;4(8):e6803. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0006803.

Acknowledgments

Cellular and Molecular Immunology laboratory, Department of Laboratory Medicine and Pathology, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, MN, staff for the help in performing the clinical testing for the patient and parents, and Numrah Fadra for help with visualization of the gene fusions. This work was supported by Mayo Clinic’s Center for Individualized Medicine and the Jeffrey Modell Foundation for Primary Immunodeficiencies for their support of the Mayo Clinic Diagnostic and Research Center for PIDs.

Funding

This work was supported by Mayo Clinic’s Center for Individualized Medicine and the Jeffrey Modell Foundation for Primary Immunodeficiencies for their support of the Mayo Clinic Diagnostic and Research Center for PIDs. No authors have any potential conflicts of interest to disclose.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

MAC, KJC, EDW, AVJ, PNP, RSA, and EWK conceived and planned the experiments. MAC, MJS, ANS, NJB, PRB, GRO, and RAA carried out the experiments. JJJ, MIM, AYJ, and PNP cared for the patient. MAC, RSA, and EWK wrote the manuscript with input from all authors.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

The parents provided written informed consent on behalf of the patient to research protocols approved by the Mayo Clinic Institutional Review Board, for immunological and genetic testing included in this manuscript.

Conflict of Interest

No authors have any potential conflicts of interest to disclose.

Electronic Supplementary Material

ESM 1

(DOCX 534 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Cousin, M.A., Smith, M.J., Sigafoos, A.N. et al. Utility of DNA, RNA, Protein, and Functional Approaches to Solve Cryptic Immunodeficiencies. J Clin Immunol 38, 307–319 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10875-018-0499-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10875-018-0499-6