Abstract

Purpose

The Dallas Pain Questionnaire (DPQ) assesses the impact of low back pain (LBP) on four components (0–100) of daily life. We estimated the minimal clinically important improvement (MCII) and the patient acceptable symptom state (PASS) values of DPQ in LBP patients.

Methods

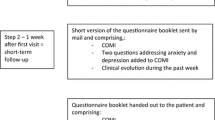

142 patients with LBP lasting for at least 4 weeks completed a battery of questionnaires at baseline and 6 months later. Questions for MCII addressed patient-reported response to treatment at 6 months on a five-point Likert scale, while a yes/no question concerning satisfaction with present state was used to determine PASS. MCII was computed as the difference in mean DPQ scores between patients reporting treatment as effective vs. patients reporting treatment as not effective, and PASS was computed as the third quartile of the DPQ score among patients who reported being satisfied with their present state.

Results

MCII values were 22, 23, 2 and 10 for daily activities, work and leisure, social interest, and anxiety/depression, respectively. PASS values were 29, 23, 20 and 21 for the four components, respectively. The PASS total score threshold of 24 correctly classified 84.1 % of the patients who reported being unsatisfied with their present state, and 74.7 % of patients reported being satisfied.

Conclusions

These values give information of paramount importance for clinicians in interpreting change in DPQ values over time. Authors should be encouraged to report the percentage of patients who reach MCII and PASS values in randomized clinical trials and cohort studies to help clinicians to interpret clinical results.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Driscoll T, Jacklyn G, Orchard J et al (2014) The global burden of occupationally related low back pain: estimates from the global burden of disease. Ann Rheum Dis 73:975–981. doi:10.1136/annrheumdis-2013-204631

Henschke N, van Enst A, Froud R, Ostelo RW (2014) Responder analyses in randomised controlled trials for chronic low back pain: an overview of currently used methods. Eur Spine J 23:772–778

Bombardier C, Hayden J, Beaton D (2001) Minimal clinically important difference. Low back pain: oucomes measures. J Rheumatol 28:431–438

Tubach F, Wells GA, Ravaud P, Dougados M (2005) Minimal clinically important difference, low disease activity state, and patient acceptable symptom state: methodological issues. J Rheumatol 32:2025–2029

Tubach F, Ravaud P, Beaton D et al (2007) Minimal clinically important improvement and patient acceptable symptom state for subjective outcome measures in rheumatic disorders. J Rheumatol 34:1188–1193

Kvien T, Heiberg T, Hagen K (2007) Minimal clinically important improvement/difference (MCII/MCID) and patient acceptable state (PASS): what do these concepts mean? Ann Rheum Dis 66 (supp 1):iii40–iii41

Van der Roer N, Ostelo R, Bekkering G et al (2006) Minimal clinically important change for pain intensity, functional status, and general health status in patients with non specific low back pain. Spine (Phila Pa) 31:578–582

Lawlis GF, Cuencas R, Selby D, MCoy CE (1989) The development of the Dallas Pain Questionnaire. An assessment of the impact of spinal pain on behavior. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 14:511–516

Marty M, Blotman F, Avouac B, Rozenberg S, Valat JP (1998) Validation of the French version of the Dallas Pain Questionnaire in chronic low back pain patients. Rev Rhum Engl Ed 65:126–134 Erratum in: Rev Rhum Engl Ed 65:363

Genevay S, Cedraschi C, Marty M et al (2012) Reliability and validity of the cross-culturally adapted French version of the Core Outcome Measures Index (COMI) in patients with low back pain. Eur Spine J 21:130–137

Genevay S, Marty M, Courvoisier D et al (2014) Core Outcome Measure Index for low back patient: full validation of the French version. Eur Spine J 23:2097–2104

Terwee CB, Bot SD, de Boer MR et al (2007) Quality criteria were proposed for measurement properties of health status questionnaires. J Clin Epidemiol 60:34–42

Coste J, Le Parc JM, Berge E, Delecoeuillerie G, Paolaggi JB (1993) French validation of a disability rating scale for the evaluation of low back pain (EIFEL questionnaire). Rev Rhum Ed Fr. 60:335–341 Article in French

Perneger TV, Combescure C, Courvoisier DS (2010) General population reference values for the French version of the EuroQol EQ-5D health utility instrument. Value Health 13:631–635

Beurskens AJ, de Vet HC, Koke AJ (1996) Responsiveness of functional status in low back pain: a comparison of different instruments. Pain 65:71–76

Cohen J (1988) Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences, 2nd edn. Erlbaum Associates, Hillsdale

Ostelo R, de Wet H (2005) Clinically important outcomes in low back pain. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol 19:593–607

Maughan EF, Lewis JS (2010) Outcome measures in chronic low back pain. Eur Spine J 19:1484–1494

Dworkin RH, Turk DC, McDermott MP et al (2009) Interpreting the clinical importance of group differences in chronic pain clinical trials: IMMPACT recommendations. Pain 146:238–244

Acknowledgments

We thank the Nukléus team and, in particular, Mrs V. Gordin and M. Demonnet, for their help and logistic support. We also although wish to thank the members of the Spine section of the French Rheumatology Society for their support in recruiting patients. The authors thank David Marsh for valuable help in editing the manuscript.

Conflict of interest

Authors declare that they have no relationship with the organization that sponsored the research. This study was supported by an unrestricted scientific grant from Pfizer.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Corresponding author

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Marty, M., Courvoisier, D., Foltz, V. et al. How much does the Dallas Pain Questionnaire score have to improve to indicate that patients with chronic low back pain feel better or well?. Eur Spine J 25, 304–309 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00586-015-3957-3

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00586-015-3957-3